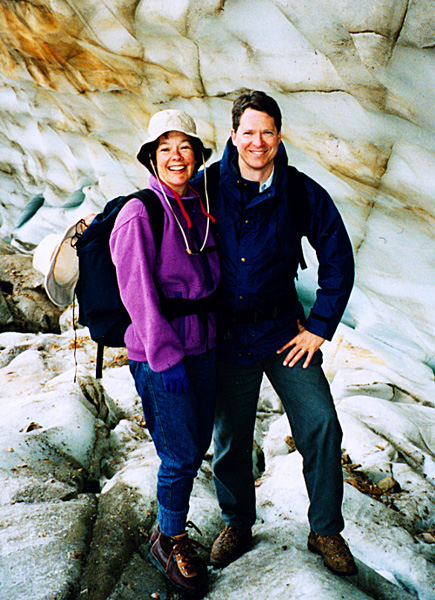

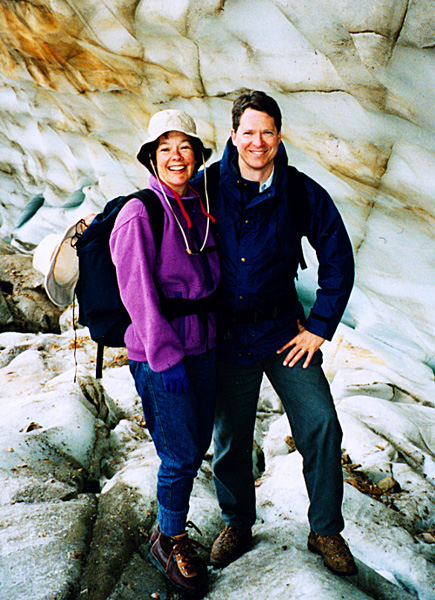

Becky and Mike at Angel Glacier in Jasper NP July 1993

Some say the world will end in fire , Some say in ice.

From what I've tasted of desire I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice, I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice is also great

And would suffice.

(Robert Frost, Fire and Ice)

Becky and Mike at Angel Glacier in Jasper NP July 1993

Beginning in 1986, it was becoming apparent to me that something significant was going wrong with my health. The medical details of the insidious onset and evolution of chronic fatigue syndrome and undifferentiated autoimmune syndrome (which are hereafter referred to as CFS / UAS) are provided elsewhere, although some overlap of illness description appearing on this page is unavoidable. I will limit my comments here regarding this illness primarily to how the major symptoms impacted my professional and personal life from 1986 to 1994.

On this page I answer the question, "Why did I stop practicing radiology and retire from clinical medicine at such a young age, and how did my job come to an end?" Although this story involves pain and suffering and a lamentable outcome, I hope that it will offer insights and understanding that might be of some use to others experiencing similar illnesses. (Even so, I can't imagine anyone, other than perhaps my closest family members and other CFS patients, actually wanting to read this melancholy tale.) It might seem that I am trying to get back at my partners or others for various grievances (no), or to get some sort of vindication (no), or at least understanding for what happened to me (yes, better understanding would always be helpful). But although I have felt defensive and even ashamed about this illness, my conscious intention here is to give an honest and reasonably complete recounting of how an invisible CFS-like illness can drastically and adversely affect one's professional and personal life, and how challenging such an illness can be for even well-educated colleagues who are called upon to deal with its consequences. I'll include many details here (though no inappropriate business secrets), because it is my conviction that to merely speak in generalities cannot adequately and convincingly do justice to the complex and difficult interactions that arose, but I have omitted names where prudence dictates.

Quietly Experiencing Early Illness: Initially in 1986, this illness was purely a private matter that concerned only me. Knowing there would be little to gain, and quite probably a lot to lose, I did not go out of my way to discuss the problem with my partners in the initial years, though I shared my anxious concerns with Paul Paulson after I was advised by my neurologist in January 1987 that I might have multiple sclerosis. It was also hardly a secret when I underwent a brain and cervical spine MRI scan in February 1987 in our own machine, and the examination was interpreted by one of our neuroradiologists. I was gradually finding it harder to keep up the extra work that my professional life required or benefited from, and that had previously been quite manageable. I recall for instance that in October 1987 I spent a fair amount of time holed up in my hotel room feeling quite sick while attending the excellent WRSNM meeting in San Diego.

Rising Difficulties With On-Call Duties: Gradually, fatigue and other symptoms of CFS / UAS began to increase at about the same time as the radiology on-call burden further escalated. We were by then going both to Providence Medical Center (PMC) and to West Seattle Community Hospital (WSCH) while on call, and we required more than one person on call at a time. I was therefore having increasing problems handling the on-call work (which could entail as many as five or six trips in from home during the night, and 12 to 16 hours spent during each 24 hour day of the weekend.) It was apparent that staying the entire night while on-call was becoming, at least for me, a necessary evil, and for a few years I slept on a couch in our radiology office in the otherwise empty and somewhat spooky professional office building next to the hospital. However, for business reasons this office space became less available by early 1990. Despite my best efforts, I was unsuccessful in persuading my partners or the hospital to provide a suitable room in Providence Medical Center for a radiologist to stay in overnight if he/she needed to do so, such as were provided to surgeons and other specialists. (I began promoting this request in 1987, but in addition to a general lack of interest, apparently some radiologists feared this would lead to a mandatory requirement that they stay overnight when on-call. I had not overtly couched my request in personal terms relating to my illness, and there seemed to be little desire or willingness to accommodate the request.) When we merged in 1989 with the Evergreen Hospital group, we proportionately reduced the number of radiologists available to cover PMC call, a reduction which I opposed. The group discussed the possibility of obtaining teleradiology capability as early as in 1989, when it would have potentially benefited me in handling the on-call burden, but unfortunately the group initially concluded it was too expensive to justify. (We did not obtain teleradiology until July 1991, well after I had stopped taking night call due to illness.)

First Work Missed—1987: After a myelogram in October 1987, which involved a spinal tap, I had a severe lumbar puncture headache, and missed two days of work, the first I had missed related to my as yet undiagnosed illness. The incapacitating headache persisted until I had an epidural blood patch placed by an anesthesiologist—a seemingly magical but strikingly and immediately effective procedure. (Prior to 1987, I had missed work for five days on "compassionate leave" when my father died in 1980, and missed a few days of work in 1984 from a severe bout of influenza, but had otherwise not taken time off for sickness, or any other unscheduled time off, since I joined in 1978.)

Increase in Work Demands, Mergers, and Practice Complexity: The size and complexity of our radiology group practice in the second half of the 1980s was increasing rapidly. There were a variety of mergers and acquisitions at various stages in the pipeline, including on the Eastside (east of Lake Washington: Bellevue, Kirkland, Redmond, etc.) and in West Seattle. Some of these were completed and some merely under discussion, some were essentially forced on us, but many were enthusiastically entered into by the group due to the perception that there would be greater safety in numbers and diversification. It was generally believed that we could better defend ourselves against the sometimes arbitrary actions of hospital administrators and hostile forces or competing physicians by getting ever larger. By 1989, we were recruiting new radiologists at a dizzying pace. We talked at some point to virtually every other private radiology group in the Seattle area about a possible merger.

My Practice Goals: I must confess that, in my simple-minded and conservative view (and reflecting my utter lack of grandiose empire-building ambitions), all that really mattered to me was being able to practice (and teach) high quality radiology, particularly in my subspecialties, at a single full-service outstanding and professionally nurturing hospital, which for me was Providence Medical Center. The office practices, which were dear to the hearts of many of my partners, seemed to me to be mostly a distraction and certainly held less interest for me, whereas the additional hospitals (West Seattle Community Hospital and Evergreen Hospital Medical Center, and others still in our sights) greatly compounded the problems of providing daytime and on-call coverage, and further diluted the effort we could devote as a group to any one site.

The Juggernaut of Expansion: But the enthusiasm for expansion—influenced by the merger mania of the 1980s, the group's understandable paranoia, the perceived allure of the golden shores east of the lake, and maybe a hint of greed—produced a juggernaut that would crush any opposition. My physical capabilities were beginning to decline while this explosion of activity was taking place, and I did not feel the heady enthusiasm that others showed. As I recall, I did not wish to appear obstructionistic, and chose to be quietly neutral—not strongly opposing or supporting any of these expansion plans. Did we really obtain greater protection as a result of all this diversification and expansion that was sufficient to offset the mounting effort and expense required? I could not say for sure, although I am certain that it made our lives much more difficult. (I must acknowledge that PMC eventually fell on hard financial times, and had to be taken over by its long-standing competitor Swedish Medical Center in 2000, long after I had left, so that some of the group's fears were validated. In addition, PSR, now merged into Radia, eventually became an even larger group practice, so the urge to expand must have remained compelling.) We made plans for a major planning session in 1988 (and another in February 2004) for the purpose of bringing some order to our chaotic progress.

Growing Frustrations: By mid-1988, I was deeply frustrated and distressed by my still undiagnosed illness. With foresight acquired from 10 years experience in this group, I was still discussing it very little with my partners. One of my partners, perhaps quietly assigned the task, took it upon himself to discuss with me over lunch what I was experiencing. I reviewed my "progress" to date with him, mentioned the urological evaluations I was undergoing (May 1988) and the other inconclusive testing, the lack of a firm diagnosis, and my evolving limitations. When he had heard what he wanted to know, I was disappointed to see his interest rapidly wane, and he proved eventually to be one of my harshest critics.

My neurologist passed me on to a psychiatrist in the summer of 1988, advising me soon after that he "could do nothing further for me", beginning a long and humiliating phase in my life (which I have discussed further elsewhere). Despite the stresses of the practice, I loved my work, but my stamina and endurance were slowly ebbing away at a time I needed the greatest possible physical capability.

We had a nice family vacation to Colorado in the summer of 1988, I continued to attend operas, I made short outings in my sea kayak, I even tried to make short hikes occasionally (such as Klapatchie Park in MRNP in October 1989, while the West Side Road was still open). To any casual observer, I appeared healthy. How could there be any legitimacy to my perception that my physical ability was diminishing significantly from illness?

In December 1988, during a particularly stressful night of radiology on-call, I developed the first of many subsequent bouts of the cardiac arrhythmia, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF). Hoping that I would not get called back to work again during the night, I went to the PMC ER at 2 AM for several hours of treatment.

I recall a state of intense anguish in about 1989, weeping in our basement at 2 AM out of the deepest possible frustration that I could neither change this gradual but relentless deterioration, nor explain it even to myself, much less convince any medical professional that it was a real medical non-psychiatric disorder.

Paucity of Objective Findings and How to Characterize My Illness: Still in 1989, there were essentially no positive laboratory or physical findings, aside from persistent fasciculations, some once-convincing mild spasticity on my left side which (so it appeared) was now discredited by my neurologist, a few bouts of PAF, and some apparently unrelated cervical disk disease. During 1988 – 1989, I locked horns repeatedly with my psychiatrist, advising him Cassandra-like of my well-founded fears of an approaching professional crisis, and of the real losses I was already quietly taking, particularly in my formerly vigorous recreational and athletic life, and in my peace of mind. But there was no dissuading him from a psychiatric formulation in the absence of input to the contrary from my neurologist. The psychiatrist suggested that I have another general medical evaluation, which was done in January 1989, but this came up with no additional findings (including remarkably a still-negative serum ANA test for autoimmunity), and my internist gently reinforced the prevailing opinion that I was in good hands with the psychiatrist.

Becky Trains in Ultrasound: Fearing with very good reason that we were facing an impending loss of my professional income, and having no significant disability insurance at the time, Becky and I in mid-1988 made the decision that she would return to school to train to be a diagnostic sonographer. This was a painful decision to us both, because she had for so long enjoyed a pleasant comfortably middle-class existence sheltered from the workforce. After exploring her options, she decided she did not wish to return to teaching biology or French (as she had done when I was in medical school), and also ruled out law school or paralegal training. Sonography was a line of work that I of course knew a great deal about, and it would at least make good use of her prior biological science background.

She started taking courses at Seattle University in September 1988. (I recall that my psychiatrist—still unaware of my eventual medical diagnosis—gently implied that I had in effect recruited my frightened wife into my own delusional belief system, and that this might pave the way to wrecking our marriage. Fortunately, Becky had much greater confidence in me than my physicians.) Her classroom "didactic" year lasted from 1988 to 1989. This was followed by an internship-like year of clinical rotations ending by September 1990—she did these rotations at the Virginia Mason Clinic, Swedish Medical Center, and the Seattle VA hospital. The clinical rotations further raised our stress levels and were a tough time for her— she experienced some stress-related conditions then, including neurodermatitis—but she bravely soldiered on.

Becky Certified and Employed in US: After completing her training, she earned certification as a Registered Diagnostic Medical Sonographer or RDMS from the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers, which was awarded October 20, 1990 (including specialty endorsements in OB/GYN and Abdominal US). She also earned echocardiography certification (as a Registered Diagnostic Cardiac Sonographer or RDCS from the same organization). She worked a little in December 1990. She graduated from Seattle University cum laude with a B. S. degree in Diagnostic Ultrasound, awarded March 21, 1991. I was proud of her hard work, but deeply distressed to have caused this drastic change in her life.

She went to work as a part-time sonographer at a few clinics, beginning in April 1991. However, she soon settled on working part-time for Puget Sound radiology (PSR) and for PMC, supervised by me and the other radiologists in my group, a tough job that lasted from May 1991 until she resigned in June 1994 when I resigned my own job. (We both felt that she was then more needed at home.)

Modifying Responsibilities: By 1989, I found it necessary to begin backing away from volunteering for the kinds of ad hoc and mostly after-hours projects that I had done extensively for our practice in prior years. (I had already given up the directorship of ultrasound in 1988, passing it after 10 years in the position to the well-qualified Bill Marks.) However, my ongoing service on our group's newly formed executive committee, from July 1989 to April 1991, added yet another frequently held evening meeting to my list of important commitments, and I continued to shoulder a large burden of clinical responsibilities in the group practice.

Seeking Fair Scheduling: As late as November 1989 and again in March 1990, I performed complex "productivity" spreadsheet analyses that were helpful in demonstrating the rather marked scheduling discrepancies existing among our various sites, and that helped us decide how to distribute our radiologists among them. By this analysis, the hospital positions such as my own were significantly undermanned. One highly touted non-hospital site in our practice, which required two radiologists to service, was only earning about $11 per radiologist's hour worked there. As one of my partners was fond of saying, we lost a little on each patient, but made up for it in volume.) Such dispassionate critical analyses probably did not endear me to the individuals whose oxen were being gored, but I always tried to put together objective facts, and let the chips fall where they might.

Recruiting Nuclear Medicine Physicians: I was glad to have Dr. Marie E. Lee join our practice in August 1989, as she was also a nuclear medicine subspecialist who could be of great assistance to me. I was happy to see her marry in February 1990, and was extremely disappointed when she decided by April 1990 to leave to return to her former practice. (Ironically, it subsequently proved to be quite difficult for the group to find a nuclear radiologist, especially one with the level and diversity of skills that I brought to the group, thus helping to preserve my precarious employment for a few more years.)

Further Difficulties with On-Call: Struggling to keep up with the rising on-call load, I slipped up toward the end of an especially busy night in 1989 in a minor way regarding my response to a case. A few hours later, I was surprised to find myself called on the carpet by a partner, who had recruited a more senior partner to serve as a witness. (In fact, this witness soon expressed regret at having being dragged into this unnecessarily zealous and humiliating confrontation.) Nevertheless, I knew by then that I could not continue with the status quo, and had to seek at least some degree of help for my on-call responsibilities. In August 1989, I quietly began seeking other partners who would be willing to take some of my night on-call assignments for pay. Initially this was mostly to ease my rising discomfort, but over the next year or so it gradually evolved into absolutely indispensable assistance. I did not seek formal approval from my group for this arrangement, since these were private transactions between me and the several willing partners who wanted the substantial extra income, but one of my partners did eventually challenge me on its legitimacy. What could I say?—I looked well, and still could not explain why I was doing this to anyone's satisfaction, and could only respond that I was the one paying for the service and the other partners were free to object if they wished.

Incorporation of Our Group Practice: The partners were, by May 1989, transformed by our incorporation into corporate shareholders and directors, but I'll continue to refer to them as partners out of old habit. (I prefer the collegiality and close working relationship that the term partner implies, compared to the coldly impersonal corporate terms.)

Group Provisions regarding Disability: My partners began in July 1989 to discuss existing policy and to debate potential changes to the benefits that the group would be obligated to provide to a disabled partner. This caused me some acute discomfort, as I was still in a leadership position and found myself explaining our long-standing policy that might end up benefiting me somewhat. The group voted in new rules to reduce its commitment to disabled partners, the timing of which seemed specifically aimed at me. Interestingly, one of the partners developed a medical condition in mid-1989 requiring a period of rest during the middle of each working day, and the partners readily agreed to accommodate this request with little discussion. (His illness was objectively diagnosable by laboratory testing, unlike mine at the time, although the impairing fatigue claimed was, like mine, a subjective complaint.) It became apparent that partner concern over the financial and scheduling impact of having one or more disabled partners was rising. At some point we also faced the question of how to handle maternity leave—was it a disability or something else? Our male-oriented bylaws were silent on this subject (and I do not recall exactly how this was settled).

Personal Adaptations to Illness—Seeking Solace in Great Literature: I was also in the process of gradually shifting how I spent my leisure time, since I was no longer able to engage in many of the vigorous outdoor or athletic activities that I had previously enjoyed. Perhaps inspired by Becky's religion course at Seattle University (a mandatory part of her ultrasound curriculum at that Catholic institution), I decided to begin reading some of the great classic literature that I had previously neglected. I began with the Old and New Testaments of the Protestant Bible, specifically the excellent NIV Study Bible, which I read cover-to-cover in 1989 – 1990. Recognizing that this great work has influenced our culture and literature probably more than any other, I had always wanted to read it (at least since college when I read Moby Dick, a novel full of Biblical allusions). In addition to the sheer pleasure and enrichment provided by such reading, these ancient works seemed comforting to me and provided a kind of escape from the increasingly agonizing realities I was facing in my contemporary life. In about 1989, I began making summaries of the major books I read, including eventually the Bible, Herodotus, Homer, Plato, Thucydides, Plutarch, Aristotle, other classical Greek works, etc., many of which have ended up on my website.

Further Stresses: With the Bible on my mind, and trying my best to complete an assigned task relating to vacation scheduling, I made an innocent mistake by including a light-hearted Biblical allusion in a lengthy proposal I sent out in May 1990 to my partners. One of them, who often seemed unhappy with our group and didn't like my scheduling proposal, took offense, implying in a physically threatening letter he sent me that I had been blasphemous. I did not respond, but mused on the irony that such a hostile and unsupportive encounter was triggered by the interest I was taking at the time in the Bible.

The year 1989 also sadly brought about events leading to an estrangement from a close relative which lasted for more than 15 years, and which greatly added to my general distress. Discord in my original family also led Becky and me to make plans to sell the San Antonio condominium we had purchased for my parents, and which my widowed mother had continued to live in (longer in fact than in any other home she ever lived in). This sale took place in October 1990, though my mother continued to live there for about two more years, renting from the new owner until she married her second husband.

Focusing on the Essentials including SPECT: Professionally, I continued to do my best to perform my most essential responsibilities as the director of nuclear medicine. In 1989 – 1990, I spearheaded the evaluation and selection process leading to the purchase at PMC of a much needed Siemens LFOV Diacam SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) camera, selected in November 1990, and delivered in about June 1991. This sophisticated but expensive instrument, which I had long lobbied for as an essential upgrade to nuclear medicine (NM), would be put to many uses but was especially needed for cardiac NM exams.

A Diagnosis Is Made: In May 1990, after six years of increasing yet undiagnosed symptoms, I learned of the diagnostic entity chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or "myalgic encephalomyelitis" (ME) from a May 14 TIME magazine article, and immediately realized for the first time that this was what I had. I was deeply relieved at first to at last have a name to give to my mysterious collection of symptoms. However, the unfortunate name chronic fatigue syndrome, which many patients justifiably regard as trivializing a serious illness, was soon to prove itself problematic for me as well. I began to do library research on this condition under its various names (including epidemic neuromyasthenia), and started to compile a collection of articles and citations. In June 1990, I wrote my former psychiatrist (whom I had stopped seeing in 1989) and my neurologist Dr. C regarding this new revelation, and provided to them a well-selected bibliography (which was the beginning of a much larger bibliographic database that I continued to compile for many years.) To my great disappointment, my psychiatrist advised me when I later saw him that he was a busy doctor practicing outside of academia, and did not have time to look over the information I had sent him. (The concepts associated with the disorder of CFS disrupt the traditional mind/body dualism, and threaten the already shaky profession of psychiatry. But I was very disheartened at his apparent lack of intellectual curiosity regarding the condition that had so affected his physician patient.) I saw the neurologist in late July, was found to have a negative EMG, and decided by then that it was time to seek another kind of physician who knew more specifically about CFS.

Request For On-Call Relief Provokes a Crisis: By summer 1990, I was experiencing extremely distressing flu-like symptoms and fatigue, and was nearing the end of my rope as a full-time worker. One day in 1990, I had to ask a skeptical partner at 3 PM to be relieved of work for the last two hours of the day, and this was not well received. My luck also finally ran out on being able to informally purchase call coverage as of mid-July 1990, and I finally wrote the group president Dr. Garrett on July 16, advising him of the nature of my illness (which we had previously only informally discussed). I included an explicit request to be relieved of night call by allowing me to pay others to take it (although I still hoped to take daytime weekend and holiday call). There was no way for me to sugarcoat and make palatable what I knew was an incendiary request to this overstressed group. And there is probably no other illness for which there is such an enormous gap in perception between the fluctuating incapacitation the patient experiences and what can be objectively observed by others. In a seemingly malign response to my first substantive request for help directed to my group, I was subsequently assigned to four consecutive nights of on-call, 105 consecutive hours of work total (Friday 7:30 AM to Tuesday 5:00 PM), centered on the upcoming Labor Day weekend, an utterly impossible task for me to accomplish by that point. (In fact, I had argued for some time that no partner should be asked to endure such an inhumane assignment, which could only lead to poor medical performance.) When I made a subsequent written request August 14 to be relieved of this assignment, the partner who prepared the daily schedule met it with an outburst of anger and hostility. Some of the partners, perhaps fearing the open-endedness and unprovability of my claim, were already lining up to summarily eject me from the practice as a result of this unacceptable request.

Rheumatology Consultation: After asking around, I learned of a rheumatologist Dr. Philip Mease who had made a point of learning more about CFS. Having reached a crisis point with my group, I went to see him August 23, as recounted here, and he soon confirmed the working diagnoses of CFS. However, he added the diagnosis of UAS. (The unexpected additional diagnosis, undifferentiated autoimmune syndrome, was based on positive evidence for autoimmunity, including a strongly positive ANA test.)

Debate and Hostile Opposition: My rheumatologist did his best to go to bat for me, calling the group president to discuss the diagnosis and its implications with him. The group executive committee, of which I remained a member, discussed that same evening the many ramifications and possible ways of resolving this problem. Did I need more medical evaluation, and could the illness be documented better? Should I resign as a partner/shareholder and be hired back as a part-time locums (since our bylaws made no provision for partial disability)? Should I be put on leave of absence? (This would have accomplished nothing for me.) Were there any partners who desired the extra money enough to be willing to cover my evening on-call assignments for pay?

When the problem was discussed before the full group on August 29, one partner, with whom I worked closely, voiced exasperated and frankly hostile opposition—he viewed my request as utterly without merit, akin to a claim of what he suggested used to be called hypoglycemia. (As I had never mentioned this particular diagnosis from my past, and as there was virtually no resemblance between my current autoimmune illness and the syndrome of hypoglycemia, I wondered in passing how he was able to draw such a comparison.) This would only be the first of several withering encounters with vocal opposition and denunciations expressed at our group meetings (or "struggle sessions", so they seemed) resulting from my invisible illness. Fortunately for me, Dr. Garrett accepted the task of taking the night hours of my on-call assignment over the Labor Day weekend, for which I was grateful. He would not allow me to compensate him for this, and I worried that his generous act was creating an unrepayable indebtedness that would lead to further problems.

Preliminary Recommendation for Termination: A subcommittee was appointed to try to resolve the issue. Its harsh conclusions in late September 1990 took a hard line against allowing special dispensations, opposed creating a new category of partial disability, and advised that the group should assume no responsibility for helping me find call coverage for pay. Of course, had I been successful in continuing to arrange paid call coverage on my own, I would never have brought the problem to the group's attention in the first place, so this amounted to a recommendation for termination.

Decision to Provide Call Coverage For Pay: Fortunately, the group as a whole reluctantly agreed to temporarily seek volunteers and if necessary to assign my night on-call assignments to other partners, who would be paid by me at a floating and negotiated rate for their work. I felt now like damaged goods, and I would never again have the standing that I enjoyed in the practice prior to initiating this first plea for partial disability status. Of course, I would readily concede that the on-call work, especially at night, had become quite onerous even to a healthy partner, and that the partners were all stressed by the workload and escalating complexity of the practice. What I had requested and was granted seemed like an extraordinary concession, even though I paid quite dearly for it.

First Substantial Daytime Work Missed: I limped along in this humiliated state in September and early October 1990. However, by this point the effects of my illness, and the adverse effects of performing the maximal possible work load, were producing a cumulative fatigue and flu-like effect that I could not recover from. I informed our executive committee on October 18 that I might soon be forced to cut back further on work. I reached a state of utter exhaustion and illness by noon on a weekend day of call on October 20, and was unable to continue to work until the scheduled changeover time of 5 PM. Barely able to stand, I called in the radiologist who was already scheduled to take my night on-call. The time had come when I needed to ask for further relief from work duties.

However, I was out sick from ongoing severe symptoms during the following work week, missing the first full weekdays I ever missed as a result of symptoms of CFS / UAS. This angered the group president, who was distressed that I was not available to work when scheduled—he implied that I had some control over my illness, and referred to my absence as "taking optional days off". My rheumatologist wrote a follow-up letter to him on October 25, spelling out the specifics of my autoimmune diagnosis, including the significantly positive ANA, and advising the group to accommodate a partial disability status.

I underwent a repeat LP also that day, which caused another severe LP headache eventually requiring another epidural patch on October 30 (this LP also did not provide any conclusive findings). I was unable to work up to October 30, and some of the group members were ready by then to declare me disabled and terminate me from the practice. I was teetering on the brink of the abyss, and it was very unclear whether I would be allowed to return to work at all, even though I attempted to do so on October 31.

Should I Fall on My Sword? The onset of compassion fatigue in some of my partners seemed to have occurred with remarkable rapidity. According to the traditional warrior ethos that seemed to guide some of my robust partners (our president for instance was a former fighter pilot), this would have been an appropriate time for me to fall on my sword like the disgraced Antony, thereby sparing my partners from further exasperation and irritation.

Concerted Appeal to Allow Part-Time Work: On the advice of Paul Paulson, however, I instead prepared and circulated to the partners on November 1, 1990 a 55-page packet containing a bibliography and certain key articles (cited below) dealing with the then-current state of knowledge regarding CFS (though not of UAS). This included the recent TIME magazine article, an abstract suggesting it was a retroviral illness (an hypothesis that subsequently did not pan out), a major review article on how to treat CFS, an article by Nancy Klimas et al discussing the immune abnormalities found in CFS, an article by Hickie et al arguing against a psychiatric interpretation of CFS, and the major review article by Henderson et al on the quite probably closely related condition, epidemic neuromyasthenia.

I included a cover letter which contained an apology for being out sick, a more complete description of my medical evaluation to date, and a further defense against the possibility that this was a psychiatric illness (which would have been the kiss of death in my group). I presented for the first time a proposal to allow me to work half-time and to be paid accordingly, working half-days, and having my pay further docked to pay others for taking my now half share of on-call assignments. This would allow me to continue to practice good medicine (with minimal risk of mistakes), to do my administrative duties, to develop the new NM SPECT service, etc. I promised that if this arrangement did not prove satisfactory (and there was no precedent in our practice for it), I would accept being terminated according to our bylaws regarding disability, and that I did not wish to impose an undue burden of the remaining partners.

Part-time Work Proposal Accepted: The articles appeared to be helpful in improving their understanding of my disorder (which after all had no radiological manifestations that they could relate to). There was one interesting side effect: a partner sitting next to me at our subsequent meeting made certain he did not accidentally drink out of my water glass! The proposed arrangement was reluctantly accepted on an interim basis by the partners, and I returned to work, now part-time. Termination had been averted for the moment.

Would More Grit and Determination Have Solved the Problem? My partners were generally hard working and honorable physicians who were faced with complex problems to deal with, and from their point of view, the case that I had made was excessively intangible. (The absence, even still in 2012, of any definitive laboratory test for diagnosing CFS or its impact on a person's work capacity is a crucial lack and a serious handicap for physicians treating CFS patients. It also leaves such patients terribly vulnerable to pejorative conclusions and adverse responses.) We all know, from the movies and TV, that if a person is sufficiently motivated, and has enough grit and determination, such a person can always overcome the barriers and impediments in their way—right? Not so! Unfortunately, just like with cardiac angina, no amount of motivation or resolute determination will overcome the typical impairments of CFS, which affects the very core of one's conscious existence, and in fact such heroic efforts typically make the disorder worse. (Thus I have coined the term neurangina by analogy to cardiac angina, which is also not made better by grit and determination.)

Not a Convincing Act: To make matters worse, I was never a histrionic or vocally demonstrative person, and would not "put on a good act" of illness for their benefit, but instead tried as I always have to maintain a stoic and dignified composure to the best of my ability and to project quiet competence. While inwardly I knew that I was trying heroically to soldier on in the face of fierce obstacles from illness symptoms and harsh opposition, from the perspective of some of my partners I was barely trying at all and was placing my needs above others.

How Might I Have Responded to Another Partner Making Such a Claim? If I had been in their shoes, faced instead with another radiologist's claim of disability due to CFS / UAS and the potential practice disruption that this might cause, I am not sure what I would have ultimately done. However, I can say with confidence that I would have tried at the least to do the following:

Regarding my own case, I believe that my work performance, manifest motivation, on-the-job reliability, and premorbid behavior had been beyond reproach prior to August 1990.

Newsweek Article: An extremely timely cover story about CFS appeared in Newsweek, in the November 12, 1990 issue, entitled "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Debilitating Disease Afflicts Millions—And the Cause Is Still a Mystery". I was truly relieved that at last the medical condition I was experiencing was getting real publicity and a sympathetic treatment, though this brought little further professional benefit to me.

Complexity of Insurance Claim versus How the Group Should Compensate Me: Going half-time also prompted me to file a claim to our disability insurer. Protracted and confused discussions ensued as to what exactly to do with me and my PSR compensation, and I will not try to recount the details here, which are largely opaque to me. It was unclear how to coordinate my PSR compensation with respect to the "elimination period" of the disability insurer. There seemed to be endless unsolvable problems and barriers to a successful resolution, and undoubtedly the leadership of the group spent a lot of their scarce time struggling to find a solution. However, I made every possible effort to help them devise an equitable approach to handling my situation. I was often made to feel that my problem was a great burden to the group. At one point, I asked to not receive further compensation until they resolved the issue of how to compensate me, as it was (incorrectly) implied that I was being overcompensated (though I had no control over this).

Ostracism, Bad Vibes, and Damage to My Professional Reputation: Some of the non-radiologist attending physicians that I had known and had enjoyed cordial relations with for many years seemed to begin going out of their way to avoid me. When I asked one of my long-standing surgeon colleagues about his new reserve in dealing with me, he indicated that one of my partners had told him that I was mentally ill. I was incensed at being so inexcusably and unfairly characterized by one or more unidentified partners. Perhaps some members in my group felt they had to exercise damage control—bad vibes through no effort of my own were spreading outside our group regarding how adversely I was being handled by them. In any event, I had the impression that the excellent professional reputation that I had worked so diligently to earn and retain was being undermined, whether intentionally or as a side effect of ignorance by some of my partners. I asked to meet with the medical director of PMC (Dr. McKee) a few times, and had my physician Dr. Mease update him by letter in 1990 on my condition, in order to maintain clear and open communications with him and to persuade him that I was still in control of my faculties, not contagious, and working hard as always for the hospital's benefit, etc.

Overscheduling: Encountering an intense workload that lasted as many as 9 1/2 hours per day, far past the "half-time" hours for which I was ostensibly scheduled and paid, I once again protested in January and February 1991 that I was being overscheduled. I presented tangible evidence of this to the group: a stack of 108 cases I had individually interpreted on one of my so-called half-days, and 115 on the following half-day. These cases included radioiodine therapies for cancer, ultrasound-guided biopsies, nuclear cardiology and US exams, and other intensive cases, along with interpretation of numerous chest films, etc., and I was also presenting at conferences and performing my usual administrative duties. I was becoming concerned that the marked stress of such a high workload might worsen my illness, and, as in the past, I was also worried about the potential for making mistakes while working in such haste. Not only could this be potentially risky for patients, but mistakes could and probably would be used against me by my more hostile opposing partners.

Why Did I Have Hostile Opponents in the Group? This is a reasonable question which I can only offer speculations about. I was a nice enough guy, and had always tried to be fair in my dealings with my partners. The most likely explanation was the obvious resentment caused by the perceived burdens I had inflicted on my partners relating to the burdensome on-call schedule and the time they felt they were wasting hassling over how to deal with my improbable claim arising from an invisible and controversial illness. I had also caused frictions by consistently advocating a high standard of practice that could reduce the bottom line of dollar earnings. And because I was one of the highly compensated partners, a new associate brought in to replace me would cost less, and might thereby improve the group's shrinking bottom line.

More Adversity—Would Resigning Improve My Health? Although I could not be certain, I felt there was little chance of improvement in my illness as long as I continued to work beyond a tolerable level and in an environment that was too often frankly hostile. Remarkably, the group now claimed to be overstaffed and unable to afford to hire more help, even though I was being paid only for half-time work. My influence on decision-making had for the most part evaporated.

A novel "new math" formula was proposed by the lead partner which reduced my vacation days because I was working only half-time. As frequent days off had become essential to me to promote partial recovery, this new scheme forced me to consume my fewer remaining vacation days securing days off used for recovery after working. A number of partners, along with our business manager and our department administrator, privately acknowledged to me that this new formula made no sense, but they feared opposing the powerful partners advocating it.

My partners were not evil persons, but several were quite harsh, and many of the actions taken were inappropriate and unfair. There were various degrees of support—some partners being generally or even very supportive—but it only took a few influential and vocally hostile members (the "bad cops") to outweigh the kind if sometimes ambivalent support expressed by others. I was so distraught in April 1991 from the cumulative effects of adverse and humiliating decisions taken by the group, the deliberately misleading dealings, the undermining of my professional reputation, the overscheduling, and the illness itself, etc., that I came close to resigning. I was reduced to tears of utter frustration when I informed the lead partner that I could no longer continue to fight him and the group on my own behalf while trying to do the important work assigned to me.

Limited Advocacy and Legal Recourse: Throughout this process, I was less and less in a position to represent my own interests as a result of illness, overwhelming workload relative to my symptoms, and the destructive effects of vocal critics. I did not have a strong mentor or advocate in the group who was in a leadership position and who would consistently and visibly come to my defense. A few partners advised me that they thought I was being unreasonable and too rigid in my expectations. I did not make use of an attorney, which might have been a mistake. However, had I done so, it might have alienated the more ambivalent partners, and initially there were probably few legal grounds on which I might muster a strong defense.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law on July 26, 1990, but its provisions became effective for an organization like ours having 25 or more employees only on July 26, 1992. Although it might ultimately have been helpful to me, I elected not to invoke this law even when it finally applied to my case—I knew that having my employment imposed on the group by governmental fiat would be intolerable.

Further Deterioration in Relations with My Group: Using the same kind of analytical skills that had earlier been quite helpful to the group, I developed and proposed in January 1991 a simple arithmetical method for assessing the value of call (suggesting it might be worth say 25 – 35% of total income), but this plan was rejected. In retrospect, I probably should not have involved myself in this effort, but I had been respected in the past for developing objective and dispassionate analyses when the group was wrestling with difficult problems. I was told by the president at a directors meeting in May 1991 that, while it might be important to me to have a fair formula, it was not important to the group. At the same meeting, I bitterly remarked that the group had made me fight over every aspect of my disability: whether my problem was a legitimate medical illness that could cause partial disability, whether I would be allowed to continue to work part-time, whether I would be paid fairly for the work I did, and whether I would receive a fair and adequate amount of time off from work to recuperate. Having been sandbagged and hammered at these meetings too many times, this was the last board of director's meeting I attended. I regretted taking this step, as it added further to my isolation and worsened my long-term viability in the group, but attending evening meetings on days I worked had also simply become virtually impossible due to illness.

Offer to Resign and Seeking Vocational Counseling: At the end of my first year's partial disability trial period, I dutifully offered in 1991 to resign if that were the wish of the group, but they decided to continue the status quo for six more months. Not wishing to leave any stone unturned to preserve my job, I sought the guidance of a vocational counselor. He was astounded to learn that I still wanted to keep working with PSR, given the harsh circumstances I described. We discussed possible work alternatives, but I felt that there was little likelihood that I could improve on my professional handling or quality of life by seeking radiology employment elsewhere—in any event, my physical limitations would make it impossible to launch a major and persuasive job-seeking offensive.

Proposal to Change to Hourly Work: But acting on this vocational counselor's advice, I soon proposed in late November 1991 a new and simpler approach for compensation which took into account the further decline in my stamina. I would no longer be compensated as a half-time partner (with reductions for on-call coverage). Instead, I would be considered to be on leave of absence, and would simply be paid at an hourly rate for actual hours of work performed (adjusted for the cost of fringe benefits such as malpractice insurance paid on my behalf). I would work four 5-hour days each week and not take night or weekend call—thus my scheduled workload would be only about 20 hours per week. (As fatigue worsened, I eventually asked to be scheduled only 2 days in a row, to allow a day in between for needed recovery. Thus my final schedule at PSR became a highly predictable Monday – Tuesday – Thursday – Friday.) One might keep in mind that my professional activities—including development work, courses, conferences, journal reading and other CME work—extended, as always, substantially beyond these explicitly scheduled work hours.

Assuring Reliability, Accuracy, and Safety: It had been repeatedly emphasized to me, and I fully understood, that whatever schedule I was assigned to work, it had to be predictable and performed with near-perfect reliability. I requested the 20-hour workweek schedule because I knew that it was the maximum that I was still able to handle without risking significant mistakes or intolerable exhaustion on the job. My work continued to include risky procedures for which mistakes could easily cause direct or indirect harm to the patients (wrong kidney identified for surgical removal, biopsy needle incorrectly placed causing bleeding, etc), as well as harm to my assistants (including my own wife), or to myself (through inadvertent punctures by contaminated needles, etc.) It was a constant concern to me, and undoubtedly also to my partners, that the work I did had to be performed safely and correctly. Regardless of my intense desire to continue working, doing so would have been indefensible if I were exhibiting increased errors and risk to the patients or to others, and thereby increasing the ever-present risk of malpractice actions. I constantly walked a tightrope with an evolving invisible illness, trying to find the right balance between my need to work the maximum tolerable number of hours and the need to be dependable and safe.

Acceptance of Hourly Work Plan: I knew that the only alternative to the reduced 20-hour schedule I proposed was for me to resign due to my increasing limitations, and I again reassured the group that if they did not find the revised arrangement satisfactory, I would honor their call for my resignation due to disability. This 20-hour schedule was accepted and put my working status on an easily understood basis—it also allowed my symptoms to improve a little under the reduced workload. With 100% hindsight, this 20-hour workweek schedule is what I should have asked for in November 1990. However, at that earlier point, I was still struggling to preserve as much of my position and stature in the group as I could, and felt strongly that, for instance, I wanted to be able to continue to vote as a director/shareholder.

The hourly rate I was paid was gradually negotiated downward by the group and for much of the time seemed somewhat low to me compared to skilled locums rates and in relation to the high responsibility I still carried, particularly as I was head of the nuclear medicine section and heavily involved with developing new NM services. At one point, an hourly wage was offered that was probably lower than a car mechanic's hourly rate (and the overhead costs involved in keeping me on the payroll could not possibly have justified the rate proposed). However, I was not in a strong negotiating position, and being able to work remained of supreme importance to me. The actual amount I was paid in these final years of practice was of concern to me mostly as a matter of preserving my sense of professional dignity and not wishing to feel overtly exploited.

Compensation and Gratitude: The partners were amazed to see on a report prepared by the business manager just how little I was actually being paid—my compensation for the year 1992 was less than 25% of a full partner's income. One would think that my humble compensation might have helped to lessen the resentment of my harshest critics. One of them however accused me to my face of being ungrateful for all that the group had done for me. I calmly responded that my treatment had been harsh, that I had been threatened with termination repeatedly, and that I was being paid at an unjustifiably low rate for fewer hours than I actually worked. My list could have been longer, but I was not particularly interested in airing grievances.

In 1993, I was eventually paid for some of the uncompensated hours I had worked the previous year. I once performed a private calculation pertaining to the initial disorganized period of my disability in 1990 and early 1991, and estimated that the group had altogether effectively subsidized the equivalent of about 1 to 1.5 months of my full partner's salary in the form of a self-insured disability benefit. This was somewhat reassuring to me, as it allowed me to believe that they had suffered little financial impact from my illness. For this modest initial financial subsidy, for the on-call work performed on my behalf (that I paid for), and above all for the opportunity to continue working as a radiologist at PMC, even if under adverse conditions, I was indeed grateful.

Staying Active Is Healthy but Confusing to Others: Throughout the many years of my illness, I have continued to remain as active as possible and when symptoms allow. This could create confusion and heighten skepticism in casual acquaintances and even in close friends. For example, I ran into an outside radiologist acquaintance at a hotel in Glacier National Park in July 1991 while touring there with my family, and could see that he was puzzled regarding how I could be there, knowing as he did that I was no longer working full-time due to illness. But it was rarely feasible, during brief encounters such as this, to spell out to persons who knew me how the symptoms of my condition typically fluctuated during the day, etc.

Growing Information Gap: Mine is not a simple medical condition to describe, as these several elaborate webpages attest, and very few individuals will ever take the time to try to understand it. Moreover, smart persons including some of my partners were not necessarily convinced of its validity, even when presented with detailed information. There grew, therefore, a huge gap between what I had learned about CFS / UAS and what most of my friends, acquaintances, and colleagues cared to know or understand about them, and this could only lead to further isolation as the more skeptical among them gradually faded from my life and support system.

Requests Made to Me to Modify My Work Hours: I was asked several times in 1991 and 1992 (for valid and understandable reasons) to work noon to 5 PM, but I regretfully had no choice but to decline, as my symptoms by then had taken on the pattern of being maximal in the mid-afternoon. From my point of view, the best compromise on caseload needs versus my symptom-limited capability was for me to work from 9 AM to 2 PM. I knew that a schedule requiring me to work later than 2 PM was bound to fail and lead to greater criticism. I offered to continue working on NM cases after hours from home, especially the essential nuclear cardiology exams, using a remote workstation, but this was declined by the group because the technology was deemed too expensive.

Stable Productive Work 1992 – 1993: I had little partner assistance in developing the procedures for the new SPECT camera (installed in 1991), but did my best, and believe we had a good service, including our new cardiac SPECT exams. I was trying my utmost to keep my eyes straight ahead, to keep my nose to the grindstone, to avoid wasted efforts and counterproductive conflicts with difficult people, to keep the quality of my procedures and interpretations that I performed high, to avoid malpractice, and to focus relentlessly on meeting the essential requirements of the job for the limited hours I was working. In this effort, it is my opinion that I did a good job during the limited hours I was assigned to work.

Moreover, I was still spending a substantial amount of my free time trying to keep up as usual with the advances in my subspecialty fields, reading journals and attending important meetings and courses (including for instance the annual WRSNM meetings, the annual Swedish OB/GYN US symposia in 1991, 1992, and 1993, and, in 1994, the Body CT conference), satisfying CME and licensure requirements, and upgrading MOBUS in 1993.

Compared to the turbulent crisis years of 1990 and 1991, the years 1992 and 1993 were a more stable and productive time for me professionally (considering my limited hours), though my stamina continued to decline, and I was increasingly lonely on the job, feeling like an outcast.

Voting Status: Although I was no longer attending the evening board meetings, I continued to express a strong desire to remain a shareholder and director, though on leave of absence status. I was no longer actually attempting to vote, but I wanted to believe that I still could do so, at least on any critical issue that pertained to my own subspecialties. In June 1993, I asked for clarification on whether I could still vote, and the group's attorney later advised the group that as a shareholder I retained my vote.

New Nuclear Radiologist: In July 1993, and acting on my urging, encouragement, and recruiting assistance over several years, the group hired a new nuclear medicine trained radiologist, Sanjiv R. Parikh. He helped to ease my NM work load during my last year in practice, and was an enjoyable colleague to work with. It was especially reassuring to know that eastside NM needs could now be better covered, since it was by then no longer feasible for me to go across the lake to Evergreen Hospital.

General Group Malaise: By 1994, the group was finding its morale and income decline further from lost contracts and practice sites, unfulfilled expectations from the hasty and rampant expansion, partners who had been slated for mandatory retirement but refused to do so (and who by then had legal grounds for opposing forced retirement), and other adverse factors unrelated to my situation.

Undermining Actions: Actions were taken in early 1994 that had the effect of undermining my position in PMC hospital as an ultrasound subspecialist, particularly regarding outpatient OB US, even though I had conscientiously attended a major OB US symposium for each of the previous three years, had done a major and needed update of my quantitative OB US program MOBUS in 1993, and had tried to remain very active in the field.

Also without initially informing me, the group entered into advanced negotiations lasting into May 1994 with the Swedish group that did US and NM, exploring having this group provide such services at PMC, further undermining my precarious position and certainly a slap in my face as the chief of NM and the former chief of US. I knew the members of the Swedish NM + US group quite well. Did my group think I might derail such negotiations?—shame on them if they did! In fact, although I fought extremely hard to retain my own employment with PSR, I did everything possible to support their efforts to find NM subspecialists who might eventually take on my roles. I strongly supported the hiring of new NM partners Marie Lee and Sanjiv Parikh, and I never acted in any way that could be interpreted as sabotaging their goals or promoting my self-interest to their disadvantage.

Worsening Symptoms: By early 1994, my CFS / UAS symptoms had left me in a state of hanging on to my practice by the slenderest of threads. I would often quietly detour to my office between cases and lie on the carpeted floor for 2 or 3 minutes, desperately trying to recover enough strength to continue on with the next US or NM case already awaiting my participation. I would also frequently lie on the floor after my work was done for an hour or more (off the clock, of course) until I had recovered sufficient strength to drive home.

No Complaints about the Quality of My Work: To the best of my knowledge, during my period of partial disability from 1990 to 1994, there were no complaints of any significance from my partners or from any attending physicians, patients, or staff, regarding the quality, thoroughness, professionalism, or expertise of my work. There was only the oft-stated and understandable dissatisfaction that I was simply not available enough of the time to fully meet the needs of the group, especially in NM.

No Significant Work Missed: After going part-time in November 1990, I missed only a trivial four hours of my (reduced) work assignments due to illness.

I Am Asked to Resign: On May 19, 1994, I was advised by our business manager—who had inexplicably been assigned this distasteful task—that a majority of the group had voted for a final ultimatum: I must either return to full-time work, or tender my resignation as a director and shareholder. Although returning to work full-time was impossible, I felt a trace of reassurance that this request implied that the partners still had confidence in my intrinsic abilities, if I would only put aside my claim of illness.

Why this request now? I can't be certain, but it seems likely that the group was feeling by then more confident that in Dr. Parikh they finally had a full-time worker who could replace most of my essential NM skills. They may also have wanted to clear the decks for the other possibly incoming subspecialists mentioned.

Resigning as a director and shareholder would: (1) irrevocably take away my vote in a group in which I had provided much skilled leadership, even important votes dealing with NM policy and ethical matters that might directly affect my practice (and I had repeatedly emphasized the importance of my being able to vote); (2) add further to my humiliation; and (3) leave me in the status of a temp worker, vulnerable to termination at a moment's notice. And since it was costly to the group to buy out a shareholder like me, and other buyouts were already in progress at a time of financial belt tightening, there seemed to be very little that the group had to gain in taking this action, other than to make it easier to legally terminate me. Judging by recent actions taken that had undermined my roles in US and NM at PMC, it seemed clear to me that a majority in the group had decided they did not need or want me to stay on any longer as a part-time partner.

Should I Keep Fighting? I was aware by this point that the Americans with Disabilities Act could potentially offer me considerable protections, if I chose to invoke it. However, I felt I had to honor my oft-stated promise to resign when asked, I was by then quite ill and exhausted from the long struggle, and I just had no fight left to give.

Final Resignation: I talked things over carefully with Becky, and with her agreement tendered a letter of resignation to the group president on May 23, citing illness and the many adverse factors resulting from it that now prevented my staying on even as a temporary worker.

Partner Responses: Some members affected surprise about this resignation, or claimed a sort of plausible deniability regarding participating in the call for me to resign, but the group president acknowledged that my response was understandable, given the recent developments and all that had gone before. He had initially been quite angry by requests I made resulting from my illness in 1990, but often told me subsequently that he was one of my best supporters, and that he had done all that he could on my behalf. I considered him something of a friend, having been to his home on several occasions, and certainly he was a respected colleague. But the recent actions that he had initiated had directly undermined my position in the hospital, and I was told that he responded with an exclamation of relief when first learning of my resignation. I received some warm comments from some of my partners, including from the president, but surprisingly many of the radiologists, even some of those I had worked closely with for years at PMC and elsewhere, took no opportunity to come by to say goodbye or to call and wish me well, having washed their hands of me. There was certainly no concerted effort made at this point to dissuade me from leaving.

Saying Good-byes: I sadly informed my "family" of technologists and sonographers, the remaining radiology staff, the office staff, and some of the hospital administrators of my imminent departure.

I sent out a final, heartfelt, and gracious letter to my radiology colleagues on May 30, thanking them for the opportunity to remain in practice even while partially disabled, expressing concern about the problems and low morale in the group, offering to be available for consultation, supporting Sanjiv Parikh's takeover of NM, regretting that I would not have the opportunity to get to know better the newest members of the group, etc.

Last Work Day: My last work day was May 31, 1994. The weekend earlier, Becky and I had cleared out my office, hauling off 24 boxes of folders that made up my massive and unique collection of radiology and medical articles. I walked out of the department at 4 PM, after 16 years of giving my absolute best effort on behalf of PSR and PMC, feeling rejected and discarded, believing with good reason that, at least among some of the radiologists, I would not be particularly welcome if I returned to visit. As of 2012, I have never returned to PMC radiology (though I have often been elsewhere on the campus). I have however shared a few nice social occasions with several former partners. This was the last day on which I practiced paid clinical radiology or clinical medicine. My successful career path in medicine had begun more than 30 years earlier, and had given me immeasurable satisfaction until my illness became an unsurmountable problem. As the clown says, 'La commedia è finita!'

Retirement Observances: There was no retirement party or any other gesture of organized group recognition despite my years of service. I received a seemingly friendly letter in July from a former group president—he was apparently still healthy and said he was looking forward to more skiing and hiking. But in his letter he suggested that he was retiring from the group for reasons similar to why I had left, apparently choosing not to acknowledge that illness was the reason for my departure. When the group a few months later put on a nice retirement party for him—a man whom I had respected and worked with closely for 16 years—the office staff was pointedly instructed to not invite me. Perhaps they feared that my ghost, like Banquo's, would cast a pall over their celebrations.

Could This All Have Been Prevented? I had plenty of time to reflect, during my illness progression while still working, on whether I might have done anything differently that could have changed the outcome. I have mentioned that less involvement in the compensation negotiations might have helped reduce tensions, but practically speaking this was impossible to avoid, given the confusion and uncertainty that my circumstances provoked. I did everything humanly possible to behave maturely and professionally and avoid conflict, negotiating only with the head of the group, keeping any discontented thoughts to myself, doing the assigned work carefully and completely, keeping up my CME and license requirements, attending courses and conferences, etc. I regretted being ill, but there was truly nothing that I could have done differently that would have made any significant difference in the final outcome on my job or professional career.

Thoughts on the Handling of Partial Disability by Professional Groups: In the spirit of trying to find any useful disability-related generalizations that might be gained from my experiences, I offer these few observations and bits of advice. Perhaps they might be of interest to members of other physician group practices:

Social Security: I never qualified for Social Security disability because, although I eventually could not practice medicine, I was always able to earn too much income doing computer work from home.

Group Disability Insurance: Incorporation of our group practice in May 1989 fortuitously provided me with group long-term disability insurance from the Paul Revere Life Insurance Company for the first time. Prior to that time, the only disability insurance that I had was a small personal policy which markedly limited coverage for "neuropsychiatric" conditions, a limitation not applicable to CFS / UAS but hard to prove. This new fringe benefit was first discussed by our group practice in April 1989. Clearly, by that point I had an obvious personal interest in having such insurance. However, the group had become quite large by then (about 15 members and still rising), and I was a small cog in the cumbersome machinery, with no significant influence on this particular decision. The group subsequently explored changing to a different brand of less costly disability insurance which might have undermined my coverage, but fortunately decided against this.

Partial and Full Disability Benefits: After going part-time in November 1990, I filed a claim for partial disability benefits with Paul Revere. The claim was approved in June 1991 and, after considerable wrangling alluded to above, benefits for partial disability were paid while I was still in practice that only partially made up for my substantial income loss. After I left practice, I was paid for what they termed full disability for six years, though again far less than I had earned in practice. I was all too aware that my disability insurance benefits were vulnerable to arbitrary termination and were probably not going to last.

Claim Denial: The claim was subsequently denied in November 2000 by the successor company, UnumProvident Corporation. They had taken over my claim after a corporate merger, and had recently launched a new corporate campaign to improve "yield management" by arbitrarily increasing the proportion of claims denied. I contested the denial, and ended up settling with UnumProvident in June 2004 on the group policy as well as on the small personal policy. My settlements amounted to a very small fraction of my original income or of what the policies should have paid, had UnumProvident fully honored my legitimate claim to age 65. In a manner somewhat reminiscent of the struggle with my radiology group, I had experienced another protracted ordeal in which I was forced to prove to a ruthless company determined to deny my claim that my illness was legitimate and significantly disabling. Of course, they cared nothing about the adverse impact this process had on me. Interestingly, they made use of a specialist in "insurance medicine", a heretofore unknown branch of medicine that deals exclusively with treating the bottom line of insurers. This nearly fourteen year saga was too painful, demeaning, and aggravating to recount in further detail. In any event, I am bound by a confidentiality agreement not to divulge the "terms, conditions, and amount" of the final settlement by this predatory company (an agreement which I believe this current description adheres to).

Off Insurance Claims: Despite the unfavorable settlement, I am relieved to no longer be on any significant disability claim, so that I do not need to worry further about spies lurking in the bushes trying to videotape me engaging in vigorous leisure pursuits. (I am not aware of this happening to me, but we have all seen videotapes made of insurance cheats.) I have chosen to include some photos in these memoirs, including the one at the top of this page, that show me doing apparently active things that I found feasible at the time, even while claiming some degree of disability. I realize that such "incriminating" activities and photos can make my story seem less credible to some persons, but have preferred to stay as active as possible, and accept the confusion and skepticism this can cause for the casual observer. My capabilities for activities while ill, however, have varied substantially during the day, and from day to day, etc. My only advice to patients with CFS, UAS, and other invisible chronic illnesses regarding filing and pursuing claims for disability, is to think very long and hard about the negative impacts that this process—which is likely to be adversarial—will have on your physical and emotional health, even if it ultimately improves your financial health.

In June 1994, for the first time since high school, I found myself unemployed and without a clear direction as to how to proceed—the linear arrow of progress in my life had been broken by a quiet catastrophe and now pointed nowhere. I was only a little beyond the "middle of our journey in life", and I had indeed come to "a dark wood where the straight way was lost". I felt cast adrift in infinite space, like the hapless astronaut Poole in 2001, but there was no evil person or malignant Hal 9000 to blame.

Over the next few months, I halfheartedly inquired of a few radiologist acquaintances in town about jobs, but understandably I received no encouragement. I knew that I was in no condition to promote myself for a clinical radiology position, and even the volunteer unpaid teaching opportunities at the UW that I was offered, and that I might have otherwise considered, would mostly be in the afternoon when my symptoms were at a peak. I could not return even to part-time work as a clinical radiologist, as a result of my unpredictably variable symptoms, including flu-like symptoms that caused at times severe levels of impairment. What would my letter of application, I wondered, say to a prospective employer? It would have to lay out my limitations that required me to have a great deal of time off and effectively made me unreliable—and reliability is a mandatory requirement for a practicing physician. (I was unable, for instance, to promise sufficient stamina to be able to satisfactorily participate in a resuscitation effort on a patient experiencing an anaphylactic reaction to IV contrast medium—a drug which we made routine use of in X-ray and CT exams, and which not infrequently produced such life-threatening reactions.) I could describe hypothetical practice scenarios in which I might conceivably have been able to work part-time for a few hours as a radiologist, along with various adverse scenarios in which any of these niches might have resulted in failure, patient or personal harm, and possible malpractice suits. In reality, there simply were no viable options available to me for resuming the practice of clinical radiology that would have been safe enough, yet that would have made any real economic difference. Although I could only strongly suspect it in 1994, my career as a practicing radiologist and as a practicing physician had ended.

The sense of loss was extreme and excruciatingly painful (and has never fully subsided). The symptoms of my chronic illness were difficult to endure, but the illness had also effectively destroyed most of what I valued in my professional life as a practicing physician, and it had impaired my credibility, professional reputation, and good name with former colleagues, friends, and acquaintances. A few months after my retirement, a former physician colleague asked me with a whiff of contempt, "I guess things have worked out pretty well for you?" But no—this was not the destiny that I had hoped to achieve in medicine! I had such profound feelings of grief and devastating loss, as a result of an illness invisible to most persons, that for many years after my retirement, I was simply unable to speak of these things without risking tears, and thus I tried to avoid or deflect idle inquiries. The medical disorder I had, therefore, led to further isolation, far beyond that which would be simply attributable to its primary symptoms or to a more conventional disability.

I did not even know what to call the bewildering state of unemployment I found myself in. I would say initially that I was temporarily unemployed, but after a few years had gone by, this could not be sustained. Was I just retired, as a former physician Dr. V cheerfully suggested? This innocuous term might suggest that there was something voluntary, perhaps even appealing about no longer working—as if I had attained the Golden Years. But that would be a cruel characterization for a dedicated physician of only 50 in 1994 who had loved his work, had spent 80 hours a week doing it, and who now felt lost without it. Was I just disabled? This was a hard sell to anyone who took one look at me and saw how active I could still be (at least during certain times of the day). Was I partially disabled? This would be somewhat closer to the facts, but still it was hard for the average person to understand why I was no longer working at least part-time as a physician. On insurance forms, I would check both Fully Disabled and Partially Disabled, and annotate the form that it depended on the definitions employed, how symptoms fluctuated during the day, etc. To label myself then most accurately, I might have said somewhat awkwardly that I was partially or substantially disabled from the clinical practice of medicine and radiology and on this basis involuntarily medically retired. In 2009, I moved past the once traditional retirement age of 65, and could thereafter with less discomfort simply label myself retired, though this does not do justice to my circumstances. I would have greatly preferred to continue practicing and teaching radiology and medicine until much older. Still, it is comforting to have become gradually less conspicuous as a non-practicing physician.

These citations are of historical interest in that they convey the state of understanding at around the time when I was forced to go part-time.

(1) "Stalking a Shadowy Assailant", TIME Magazine, May 14 1990

(2) E DeFreitas et al, "Evidence of Retrovirus in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome",

11th Intl Congress of Neuropathology Kyoto Sept 4, 1990. [this finding was not subsequently confirmed]

(3) NM Gantz, GP Holmes, "Treatment of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome", Drugs, 1989.

(4) DA Henderson, A Shelokov, "Epidemic Neuromyasthenia—Clinical Syndrome" NEJM 260:757-64, April 9, 1959

(5) NG Klimas, et al, "Immunologic abnormalities in Chronic Fatigue

Syndrome", J Clin Microbiol 1990 Jun;28(6):1403-10

(6) I Hickie, et al, "The psychiatric status of patients with the Chronic

Fatigue Syndrome", Br J Psychiatry 1990 Apr;156:534-40

(7) G Cowley, M Hager, J Nadine, "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Debilitating

Disease Afflicts Millions—And the Cause Is Still a Mystery", Newsweek November 12, 1990.