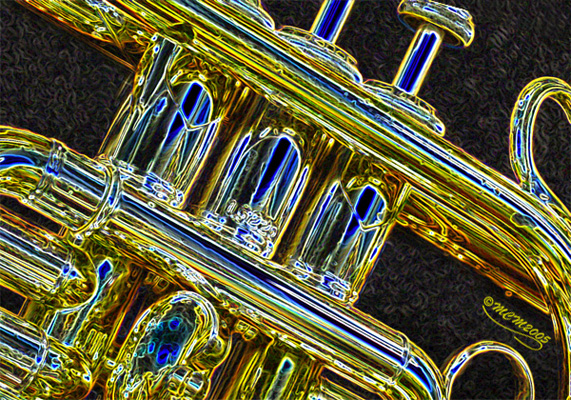

Bach Stradivarius Cornet (© Michael McGoodwin 2005)

Music hath charms to soothe the savage breast, To

soften rocks, or bend a knotted oak.

(William Congreve in The Mourning Bride, 1670 – 1729)

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!

Here will we sit and let the sounds of music

Creep in our ears. Soft stillness and the night

Become the touches of sweet harmony.

(Lorenzo to Jessica at Belmont in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice V:1)

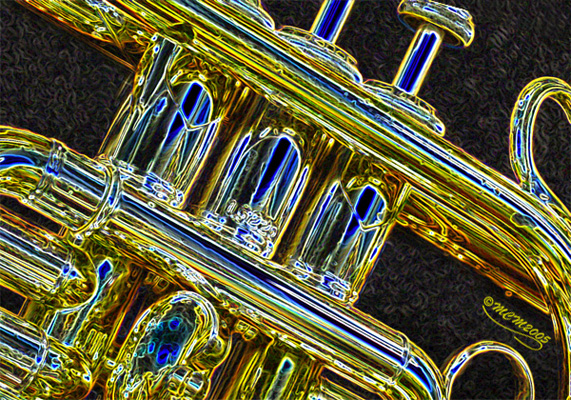

Bach Stradivarius Cornet (© Michael McGoodwin 2005)

What is music? There is no single yet fully satisfactory answer. Oxford/Grove Music Online (2014), in turn quoting many sources, attempts to explore some of the remarkably diverse conceptions: "Referring originally to works or products of all or any of the nine Muses... It may be argued that this suggests a conception of music as the quintessence of arts and sciences of which the Muses were patrons... A series of sounds and a group of compositions, and musical activity as consisting mainly of composition, expressed as the combining of sounds... That one of the fine arts which is concerned with the combination of sounds with a view to beauty of form and the experience of emotion; also, the science of the laws or principles (of melody, harmony, rhythm, etc.) by which this art is regulated... The science or art of incorporating pleasing, expressive, or intelligible combinations of vocal or instrumental tones into a composition having definite structure and continuity", etc.

Music for me is a passion that, like family and career, has played a central role in my life—I feel I almost could not live without it. It is a respectable addiction, tolerated by society. Medical research has shown that music stimulates the same parts of the brain that are activated by food, sex, and addictive drugs. The ability of music to induce such intense pleasure suggests that, although it may not be essential for our survival, it may indeed be of significant benefit to our mental and physical well-being. (See References below for exact quote from which this passage has been paraphrased.) This type of research merely confirms the obvious to anyone who truly loves and gets "shivers down the spine" from music. Music can be comforting, exciting, calming, inspiring, inciting, relaxing, energizing, subversive—it can be anything you or the composer wishes. I hope that my readers will recall musical pleasures while reading this page, just as I have in writing it.

My mother remembered singing to her infant sons often during the early 1940s, playing music such as waltz movements of symphonies, and dancing (at least with my older brother Russ). Thanks to her and her record collection, we grew up with music playing in the house—especially and almost exclusively classical music. In the later 1940s, she sang with a nice alto voice in the choir of St. Luke's Episcopal Church in San Antonio Texas under her much-beloved director Eric Harker, and especially enjoyed the rich musical tradition of the Episcopal Church. Her love of choral music eventually rubbed off on me. (I participated for a while in the church youth choir at about the age of ten or twelve under this same fine, gentle, and kindly teacher, but was not gifted vocally. Mr. Harker was thrilled many years later when I sent him a tape I recorded in the 1980s of a Seattle FM radio broadcast of the Compline Choir of St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral.) My mother's brother Russ had a considerable musical talent, and played the banjo in a Dixieland group called the Delta Kings. Although he started out as an engineer, music became dear to him and he became the only quasi-professional musician that I am aware of in my immediate kin. He inspired my brother Russ to take up the banjo in later years.

In 1951, when I was in the 3rd grade, my mother steered my brother Russ and me into piano lessons taught by Florence Bente, who lived on Harrison Street in San Antonio. My mother recalls that I played mechanically, like a wooden soldier, and for only the required amount of time, while Russ showed more aptitude and interest. The little white busts of Beethoven and other composers that we received as incentives for our efforts were not sufficient to motivate me to greater practice and skill, and the annual recitals in a white building (probably near Brackenridge Park) were terrifying and traumatic. (In contrast, I marveled in the 1970s and 1980s at the skill and effectiveness by which the Suzuki piano teaching program instilled self-confidence and public poise in our own children, by emphasizing early and frequent performance in front of peers, parents, and other adults.) I took lessons only two or three years, and as an adult have always deeply regretted that I did not acquire more pianistic skills. How I would love to be able to play complex harmonies on the keyboard with ease!—what a true waste of opportunity on the young! Since I presumably liked music even back then, perhaps this failure of achievement had something to do with less than ideal dexterity—which I also later noted even as I tried to learn typing—as well as to my lack of personal discipline and motivation, and the press of other diversions. Russ took to piano lessons more successfully and could pound out Chopin's Revolutionary Etude years later with great amplitude if not great subtlety. He also went on to become a good banjo player.

I joined the junior high school band (i.e., the concert band or wind band) at Alamo Heights Junior High School in the seventh grade. Russ had preceded me, playing trombone, but I decided to play the cornet. My parents first bought for me an Olds B-flat cornet. The director was Tommy Fielder, a inspiring bandleader bearing some resemblance to Spike Jones. He was a lively, thin, and nervous person, with a beaming smile and a wry sense of humor. My hat is off to anyone who can tolerate, much less thrive in, the cacophony accompanying a junior high school band. Like most artists, he had some interesting ideas—for instance, he liked to tell us of the therapeutic value of playing brass instruments, based on his observation that he had never known of any trumpet player dying from tuberculosis. Whether there was such a therapeutic correlation I could not now say, but no doubt brass playing built up a healthy breathing apparatus and increased lung capacity. I recall little about what kind of music we actually played during these junior high years, but I enjoyed this early experience with organized musical performance, and was glad to have had it.

Classical Influences: By 1957, I had acquired an intense interest in and enthusiasm for classical music (a love which as noted above derived from my mother's influence), and enjoyed listening to records on our stylish black Ampex stereo console. Her LP collection, which established my early favorites, consisted by then of mostly orchestral and symphonic music such as the Beethoven and Brahms symphonies, Tchaikovsky symphonies and ballets, Mussorgsky/Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition, Sibelius Finlandia, etc. Since Russ and I both played brass instruments, our record collection probably over-represented the ebulliently brass-rich sounds of Wagner, Ravel, Respighi, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, etc., rather than the more restrained world of strings, chamber music, Haydn, Mozart, etc. We had little choral or vocal music or opera back then, though my mother clearly loved choral church music. I treasured playing those records, wishing somehow that I could take on a more active part in the classical music world, and not be just a listener. Music had become my greatest pleasure, my solace and escape from more pressing or painful realities, my only artistic passion. At some point, my brother Russ enjoyed challenging me with "one-note contests"—guessing the musical piece by hearing only its opening chord—and I got pretty good at this.

No Strings Attached: It is one of the real regrets of my life that through a combination of internal and external circumstances, I had no easy opportunity to participate in a genuine symphonic orchestra with strings while growing up. Our high school offered wind band, not an orchestra with strings, and to play in the youth symphony would have involved a level of commitment and cross-town travel that just did not seem feasible for me. In high school, in fact, I avoided too open an association with those individuals who were identifiably serious classical music lovers—e.g., those who played in the San Antonio Youth Symphony or who joined the Classical Music Appreciation Club— probably because of the tyranny of adolescent self-consciousness and the need to be cool. I do not recall attending the San Antonio Symphony in high school much if at all, though as younger students we had made day-time field trips to hear it.

Alamo Heights High School Band: During my four years of high school, I played in the Alamo Heights High School Band (AHHSB). The band was led by the rather formidable—some students even said tyrannical—but generally well respected director, Earl O. "Pat" Arsers (1905 – 1978, retired in 1963, see photo to right and also a later picture copied from our 1961 AHHS yearbook). He was more of a prickly Karajan type in personality rather than a delicately sensitive Bernstein. The band met in a spacious and bright rehearsal hall, always had the best in equipment (including a state-of-the-art electronic tuning device), bass horns made of real brass, the best-made cymbals, etc. As a freshman, I upgraded my starter Olds cornet to a gleaming Bach Stradivarius B-flat cornet which I still have though now gathering dust (photo at top).

Marching Band: The band schedule combined marching with concert band activities. Late summer or early September found us sweating in the early morning hours on the dewy grass practice field, learning our half-time entertainment routine for the upcoming first football game of the season. The band played in the grandstands at every football game, and provided half-time diversions which of course few students actually watched. We wore wool uniforms in the Texas heat—these would now appear old fashioned compared to the jazzy uniforms displayed on the band's current website. As a non-football-playing band member, I must say that I quickly came to detest the way that music and musical values were subordinated—one might even say prostituted—to football, but this was Texas after all, and there is nothing more puzzling than the bizarre emphasis placed on that sport in my state of origin. (Sure, football builds character, warrior skills, teamwork, brute strength, and fitness, if you survive the injuries, but you will have to look elsewhere to find praise for this sport).

I stayed with the band despite my dislike of the marching part: the half-times, the marching contests, and the annual Battle of Flowers Parade (for which we sweltered in our wool uniforms in San Antonio's afternoon April heat, to honor the heroes from the battles of the Alamo and San Jacinto, and to kick off Fiesta Week). Through such participation, I presumably have contributed to this well known San Antonio civic celebration—sure would not want to go back to doing this, however.

Marching Band Repertoire: As a cornet player, I enjoyed much of the march and circus music at the heart of marching bands—such great John Philip Sousa marches as El Capitan, High School Cadets, King Cotton, Semper Fidelis, The Washington Post, etc.; as well as Karl King's Barnum and Bailey's Favorite and Cyrus The Great; and Edward Victor Cupero's Honey Boys on Parade. I include here an MP3 file that I created (from a mono LP original recording) of a performance of the latter march by the AHHSB, performed for the Region VI Band Contest in Spring of 1959, my sophomore year. The marching band did get to make out of town bus trips, and this was more or less fun, but I could have used more focus on producing worthwhile music. One fondly recalled vignette: the night band bus trips presented us horny and automotively deprived sophomores with a rare opportunity to pair up for the long ride back home, and I recall enjoying, for the first time in general and the only time with her, the warm full lips of a sweetly attractive woodwind player (who will go unnamed).

Concert Band Repertoire: During the rest of the school year, when we were not devoting ourselves to promoting the football team and demonstrating our militaristic roots, the AHHSB provided a very tolerable musical experience. Pat Arsers was demanding and ran a tight ship, enforced high musical values, insisted that we play in tune and on the beat, and selected a fine and ambitious body of concert music for us to play. Our repertory included many selections from the distinguished classical tradition. These included completely free-standing concert works, like Williams's Symphonic Suite for Band and Colby's Headlines. More often they consisted of overtures or excerpts of larger works: from Gluck's Iphigenia in Aulis (Iphigénie en Aulide); Bellini's Romeo and Juliet Overture (from I Capuleti e i Montecchi); Tchaikovsky's Oprichnik overture and the Finale from his Symphony No. 4; Beethoven's Egmont Overture; the Finale of Kalinnikov's Symphony No. 1, etc. We performed these works at well-attended concerts, a musical high point in my brief performing career.

Swing Band: I also played in the 18-person Swing Band during my last three years of high school, led by the competent and kindly Richard Cranford—I was first chair in my final year. We played a satisfying selection of Big Band, swing, and jazz music mostly from the 1930s to 1940s. This repertoire made less of an impression on me than the classical music I favored, but I enjoyed some of the classic hits we played, including several by Glenn Miller (In the Mood, Moonlight Serenade), Hagen and Rogers's Harlem Nocturne, and some good Dixieland selections, etc.

Iron Mike: Mr. Arsers honored me in my senior year by making me the first chair cornet—i.e., the lead cornet position. He also engineered me to be band President, a largely honorary position that was probably appointive rather than elective. It was one of the few real leadership positions I have held outside of my medical career. He liked me, gave me A's, and he also gave me one of the few nicknames I have ever had, "Iron Mike". (Iron Mike was a popular nickname in the first half of the 20th century, applied to various military monuments representing heroic men who were especially tough, brave, and inspiring, including a statue memorializing Spanish-American War veterans located on the U. Minnesota campus where Mr. Arsers attended). However, as I was not especially heroic, I think he meant to imply that I had great stamina as a cornet player and could just keep blasting away in a high range and at high volume—and hopefully in tune—for hours. Anyway, I liked the name. I generally memorized my band music, kept a steady eye on him as he conducted us, and thus helped to keep his beat and the intended dynamics with Germanic-like precision. Even if such playing lacked the greater subtlety and more nuanced sounds expected of a string orchestra, I was proud of the full and rich sounds we achieved, and hope that my contribution fully reflected the musical values he was striving for. I respected this man, and look back on him as one of the important figures in my growing up years, inasmuch as he devoted himself wholeheartedly to his job and strived uncompromisingly for musical excellence and discipline.

Missed Opportunities and Regrets: In my earlier high school years, he encouraged me to seek private lessons to improve my skills, but I never took this opportunity. I also did not practice as much as I should have, and rationalized that I did pretty well despite making little extra investment in my musical instrument outside of actual band sessions. Like other aspects of my high school experiences, I have some regrets: I wish that I had applied myself more to mastering the cornet; that my cornet had been a trumpet instead (a more mainstream instrument, although they sound quite similar); that my band experience had instead been a symphonic experience; that (speaking more hypothetically) I had been able to choose a more versatile instrument, such as the violin or French horn, to carry into a later symphonic orchestral life; and most of all, that I had been given more inherent musical talent in life. But the cornet–trumpet fit my developing musically assertive temperament pretty well, and remains the only musical instrument I ever played with any skill.

Pipe Dreams and Shadows: Although I harbored a desire in high school to somehow become a conductor (as confessed in a school newspaper article in Spring 1961), and by the time of my college years wanted even more to be a composer, these feelings proved to be unattainable pipe dreams which were never pursued. My reasoning for why I have wanted to become a composer went like this: The best of classical musical compositions are enduring masterpieces which last through the ages, are some of the finest creations of our species, bringing honor and immortality to gifted composers. Notated (scored) compositions such as Tristan und Isolde represent a kind of Platonic ideal, with an existence beyond the material world (just like the love of those doomed lovers). The subsequent realization by conductors and performers of such eternal musical compositions as actual performances (ultimately in the material form of sound waves and visual effects, etc.) represents only an approximation of the ideal. This is akin to Plato's view that most of us cannot experience the ideal world, but instead are granted only imperfect representations of it, as if viewing mere shadows cast on the wall of a cave. This view of musical works admittedly breaks down somewhat when considering more improvisational types of music which are much more dependent on the performer and the specific performance for their actual existence and success—these are exemplified by some of the great jazz works and performances by Louis Armstrong and Ray Charles. But my own preference in music tends toward classic works that are generally adequately preserved for the ages by written scores (supplemented where necessary by historically informed performance practice opinions, traditions, and sheer speculation).

When I went to college at Rice University, I largely put aside my cornet to focus on studies. There were opportunities to be an intermittent part of an orchestra on campus, but I just was too busy to consider this for the most part, and I certainly did not consider joining the Rice Owl Band. I joined in a pickup Dixieland group only briefly, but this was not my favorite style of music.

The Mikado: During my college years at Rice, the one meaningful opportunity I found to perform on the cornet was in the large orchestra accompanying a staged presentation of Arthur Sullivan and W. S. Gilbert's delightful operetta, The Mikado. This was during my junior year—Becky attended this performance on March 20, 1964. I loved the ebullient music and clever lyrics, and was thrilled to participate in an orchestra that included real strings, in what proved to be my only significant and genuinely orchestral performance.

Musical Events and the Gonzalezes: While my performing years were coming to an end, my college years marked the beginning of my active symphony concert attendance. As a rather lonely college freshman, I was taken under wing by old family friends in Houston, the petroleum economist Dr. Richard J. Gonzalez and his wife Loraine Gonzalez. They introduced me to the world of opera by taking me to the Houston Grand Opera to see fine performances of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov (in the 1961-1962 season, probably the Rimsky-Korsakov 1908 version, with Jerome Hines as Boris according to the HGO website) and of Mozart's The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte, in the 1966-1967 season according to the HGO website). Although I had less affinity for it, they also introduced me to chamber music (of which I especially enjoyed the Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor), and to other types of works they played in their home on LP records, including Poulenc's Gloria, Widor's Organ Symphonies, and others. In many different ways, these generous and intelligent mentors served for me as much desired role models, and they led the kinds of lives I partly wished to aspire to: materially comfortable, to be sure, but also enlightened, well-read, musically and artistically enriched, and diverse in their interests. They were childless, and seemed to enjoy sharing their cultural riches with me and others. When I was dating Becky steadily as a Rice senior, they took us both to a number of musical events in Houston, including Gounod's Roméo et Juliette on February 6, 1965 and probably Rimsky-Korsakov's Le Coq d'Or on April 8, 1965. (note 18)

Houston Symphony: The Houston Symphony Orchestra (HSO, also just called the Houston Symphony) was of very high quality and had some notable conductors. The lead conductors during my Houston years were Sir John Barbirolli (1961 – 67) and André (or Andrý) Previn (1967 – 69, prematurely terminated apparently after abandoning his wife for Mia Farrow). Distinguished artists in my years attending included the conductor Pierre Monteux, trumpeter Maurice André, flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal, pianist Clifford Curzon, violinist Zino Francescatti, and many others. (My mother even recalled hearing Sergei Rachmaninoff play for the HSO in the 1930s and meeting him at the time.) In about my junior year, I had a lucky break, acquiring (along with my suitemate Jim Crawford) the franchise to sell HSO season tickets on the Rice campus in exchange for free season tickets. I continued this modest sales activity throughout medical school, thus for about 6 years in all.

Boston and New York Visit: As a sophomore at Christmastime 1962, I attended a concert in Boston of the Boston Symphony Orchestra with one of my college suitemates, Jim Crawford. I remember little, but it was very enjoyable to hear this great orchestra live—wish I could have heard more. We also saw a very fine performance of Mozart's Don Giovanni at the old Metropolitan Opera House. (This revered building was located on Broadway between West 39th and 40th Streets, was last used in 1966, and was razed in 1967.) We bought standing gallery tickets for about $1.50, and were positioned to the right and just next to the stage as I recall. The Commendatore's powerful voice and role made a great impression on me. According to the online historical database of the Metropolitan Opera for our likely date of attendance (December 20, 1962), the Commendatore was William Wilderman, and Cesare Siepi, Leontyne Price, Nicolai Gedda, and Teresa Stratas also sang leading roles—a fine cast for a neophyte to hear! This was one of the greatest opera experiences of my life.

Music Reproduction Systems: A brief digression regarding the necessity for owning and playing music on expensive playback equipment: Although I would generally prefer to hear music played on a sound system of decent quality, or directly in the concert hall (provided the musicianship is good, the seats are suitably close to the action, and the coughers have already unwrapped their lozenges), I have found that the brain can often reconstruct to a large extent the ideal sound of a great and familiar work when exposed to even inferior sonic reproductions of it. I recall a time in September 1964 when my older brother and I walked into a small used book store in Aspen Colorado. The amply bearded and comfortably relaxed man on duty was playing—and I got to enjoy for a while—the lovely sounds of Schubert's Ninth "Great" Symphony, even though it played from a scratchy dusty record on an old and well used turntable and through tinny speakers. I mused that the mind has the ability to at least dimly recall a radiant Platonic ideal in music to which we have previously been exposed (especially when you find yourself on a road trip in the American West and are music-starved to begin with).

Becky and Music: As my relationship with my future wife Becky blossomed in college, she and I became more and more a concertgoing pair, which gave us one of our favorite joint recreations while in Houston. I was pleased to serve as an enthusiastic if amateur resource to help inspire her increasing interest in classical music. And I was pleased to see that she was a talented piano player.

The HSO moved into Jones Hall in 1966, the year Becky and I were married. We continued to attend the Houston Symphony regularly with our free season tickets (some earned by Becky who was still on the Rice campus for the first year that I was in medical school and had taken over the Rice franchise), and we became increasingly familiar with the symphonic repertoire.

Houston Summer Symphony: In summer 1965, I lucked into another interesting musical job: I served as a sound technician for the Houston Symphony Summer Nights concerts in Hermann Park, working under sound technician Mr. Harry Keep. He auditioned me for the job by playing classical excerpts (such as the scherzo movement from Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony) to see if I could identify the music quickly, sort of like Russ's former one-note contests. It was hot and buggy work, but very pleasing nevertheless to be backstage so close to the professional orchestra as well as circulating in the audience as it performed. This was the only paid job I ever had that pertained to music.

Other Houston Concerts: We also occasionally attended concerts of other types: organ concerts (including one of Poulenc works on February 25, 1966), chamber concerts, and church-based choral concerts (including Brahms's fine Ein Deutsches Requiem and Poulenc's Gloria), but orchestral music remained my favorite and most affordable musical experience during the 1960s.

New York Summer 1968: We enjoyed many musical performances while living in Manhattan in the summer of 1968, including free concert versions of Bizet's opera Carmen and Saint-Saëns's Samson et Dalila, both performed in Central Park. We were fortunate also to attend a performance of the Haydn Cello Concerto played by ill-fated cellist Jacqueline Du Pré (1945 – 1987), and conducted by her husband Daniel Barenboim in the recently built Lincoln Center.

Performing During Medical School: While attending Baylor Medical School, I was given the opportunity to join in the brass ensemble that Dr. Grady Hallman formed from a subset of his group, the Heartbeats, and I also tried playing with the larger group. The Heartbeats was a dance band largely composed of cardiovascular and other surgeons, including such notables as Denton Cooley (on bass fiddle) as well as John Hill, a plastic surgeon. (Dr. Hill was later accused of murdering his wife, and was himself shot to death, and became the subject of a 1981 movie, Murder In Texas.) Unfortunately, I was too busy to stick with this decidedly colorful and interesting group of musicians!

I was given a guitar by Becky while in medical school, and tried for a while to learn how to play it, but I did not make much progress and eventually sold it after moving to Alaska.

Anchorage: My last group performing opportunity came in 1970 – 1971 when we lived in Anchorage Alaska. At last, I had a little extra time on my hands, and there was a training orchestra sponsored by the Anchorage Community College that met once a week. I joined in these sessions for a while, intruding politely on the space carved out by an older engineer named Paul C., who did not take happily to competition for lead trumpet roles. The conductor Frank Pinkerton (also the director of the Anchorage Youth Symphony) suggested we alternate taking the lead parts, and this worked out well. However, I soon moved on to things that interested me more. The details I mention here partly derive from a nice article from the Anchorage Daily News newspaper dated January 6, 1971, including a photo of me with Paul C. and others that is aptly captioned "Belting it out are brasses..."

Grand Europe Tour 1972: While still living in Alaska, we attended and enjoyed numerous fine musical performances during a grand tour of Europe in 1972, including the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the Vienna State Opera, the Bavarian State Opera, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. (Trip details are here.)

I considered resuming playing the cornet in Seattle from time to time in the 1970s, and once in 1982 enjoyed playing Christmas carols with some other instrumentalist friends and singers. But the level of musical expertise and professionalism that surrounded me in Seattle was just too high, and the spark to perform on this instrument went out permanently. Thus my modest musical performing career came to a disappointing end. In another life, I might want to be a musician and composer, but in this one I have had to content myself with being a physician who happens to be an avid listener and more recently a student of musical miscellany.

Becky and I became regular concertgoers in Seattle after moving here in 1972. We have attended a wide variety of concerts, including the Seattle Symphony Orchestra for a few years, and the smaller-scale Northwest Chamber Orchestra. We have also enjoyed numerous choral performances: Bach works including cantatas, Mass in B-minor BWV232, Magnificat BWV243, St. Matthew Passion BWV244; Beethoven's Missa Solemnis; Brahms's Ein Deutsches Requiem; Fauré's Requiem; Handel's Messiah; and the Mozart Requiem K626 along with a number of his other choral works and motets. We enjoyed a variety of early music concerts, organ concerts at St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral, visiting ensembles such as the Juilliard String Quartet (1974), the Tallis Scholars (in 1998 and 2001) and the Anonymous 4, as well as other smaller ensembles at various venues.

Our principal focus gradually shifted from instrumental and orchestral symphonic music toward vocal and choral music and especially to opera, as we became able to afford it and our understanding and love for it grew. This evolution is reminiscent of the interesting controversy over so-called "absolute" music versus "program" music, which was fought out in the second half of the 19th Century (well-discussed in Oxford Music Online). Absolute music (which is ostensibly abstract and non-representational) includes nonvocal works like Chopin's nocturnes, the Brahms Symphony No. 1, and J. S. Bach's Suite No. 2 in D min for Unaccompanied Cello BWV1008 (the Sarabande or 4th movement of which was used in Bergman's hauntingly programmatic 1961 movie Through a Glass Darkly). The nocturnes, the Brahms symphony and the Bach may have their moody effects and evoke abstract feelings of appreciation, but they typically have no intrinsic program. Despite Bergman's use to such grim effect, none actually depicts a scene, image, or mood conceived by the composer. In contrast, program music is said to evoke extra-musical concepts by representing a scene, image, or mood, and includes Liszt's symphonic poems, Beethoven's Pastoral or Sixth Symphony, and Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique. (The term was traditionally applied only to nonvocal works.) Many great instrumentalist musicians might very well prefer to let their own musicality shine through rather than being lost in the forces recounting an operatic tale or choral narrative. But in general, I have found that, as I have gotten older and further removed from performing instrumentally—perhaps also because I have also heard a great deal of abstract absolute music over the years, some of which can seem a little thin—well, I often simply prefer music that lets me respond, not just at the abstract esthetic level evoked by the patterns of notes, rhythms, and harmonies, but also at an emotional level when evoked by a "program" or narrative. Thus I tend to prefer opera, choral works, and songs. Miniature tales, like short stories, can be told in popular songs and so-called art songs (lieder), such as the exquisite Gretchen am Spinnrade by Schubert, or Gestillte Sehnsucht by Brahms, and these can also be quite moving. This is my explanation for trending toward a preference for programmatic music, opera, choral, and other vocal music, even though some musical purists believe that absolute music occupies a higher plane.

Perhaps our shift in taste to opera and choral works also was a response to what was being increasingly imposed on the symphony concert audience: By the 1960s and 1970s, the growing chasm between music lovers and certain avant garde or "academic" composers had become painfully evident. It seemed to me that the typical concertgoer was becoming more and more estranged by programs emphasizing what seemed to me to be "non-musical" music such as—and here I reveal my ignorance—twelve-tone or serial, aleatory or random, other atonal or post-tonal music, and even overtly cacophonic abominations. (My apologies and admiration are extended to more advanced students of such musical genres who are able to understand and appreciate them.)

Fortunately, the world of opera seemed less affected by this trend, and performances continued to favor the classic and reliable crowd pleasers, such as Puccini's "shabby little shocker", Tosca. (Only recently has the Metropolitan Opera performed Schoenberg's Moses und Aron, while Berg's Wozzeck seems somehow appropriate for its context and even satisfying despite its serialism). I am grateful to see that in the last 20 – 25 years or so, the pendulum seems to have effectively swung back in favor of melody and some degree of tonality even in orchestral music. Meanwhile, opera appears for the most part to have remained more melodic, including relatively contemporary operas we have enjoyed such as by: Philip Glass b. 1937 (e.g., Akhnaten); Daniel Catán b. 1949 (Florencia en el Amazonas); John Corigliano b. 1938 (The Ghosts of Versailles), Thomas Pasatieri b. 1945 (The Seagull); and Adams b. 1947 (Nixon in China).

We thrilled at the chance to hear at Seattle Opera some of the individual operas from Wagner's Ring cycle (Der Ring des Nibelungen) in the mid-1970s, and several full Ring cycles in 1979, 1980, and 1981, thanks to the vision and perseverance of their general director Glynn Ross. We regarded Ross's presentations (in 1980 and in the summer of 1981) of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde as major Seattle operatic events. We grew further in knowledge and experience attending Seattle Opera during the Speight Jenkins era (1983 and onward). We especially enjoyed Seattle Opera's 1978 Norma (by Bellini); the 1988 Satyagraha (by Philip Glass); the 1989 Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and the 1994 Lohengrin (both by Wagner, and with tenor Ben Heppner); the 1993 Pelléas et Mélisande (by Debussy, staged with fantastic faux-glass props supplied by Dale Chihuly); the 1997 Werther (by Massenet); the Ring again; and the later 1998 Tristan und Isolde (with Heppner and Jane Eaglen). We have had some disappointments due to our high expectations along the way, such as the wretchedly staged Parsifal of Wagner at San Francisco Opera in 2000, and the somewhat bizarrely staged Parsifal of Seattle Opera in 2003. However, Seattle Opera has greatly enriched our lives in Seattle overall, and we have been grateful to have such a fine resource nearby. Opera is an expensive business, and attendance requires stamina that is increasingly hard to muster, so we have in recent years cut back on live downtown operagoing. We are trying instead to attend the enthusiastic and often entertaining if less professional opera productions given at the University of Washington—for instance, Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin presented in May 2009 at the UW.

Early UW Opera Courses: We took courses at the University of Washington beginning in 1975 on Seattle Opera's upcoming works, and we returned to these for several years. These were noncredit "Spectrum" courses, taught by the masterful teacher, Dr. Charles E. Troy. His lectures were illustrated by musical examples played skillfully at the piano. This was probably our first in-depth exposure to musicology analyzing the relationship between musical motifs and the characters and actions they are associated with. I recall especially his discussion of the many descending melancholic motifs in Eugene Onegin, the contrast in motifs between simpler and more sophisticated character depictions, and his enthusiasm for a truly grand performance of Verdi's Aida in Italy (in which the back of the stage opened up to reveal a parade of chariots and elephants). These courses stand out in my mind as the model of how opera should be taught to lay persons. In 1979, we also took a Spectrum course that proved less satisfying, on Wagner's operas and musical development, taught by a German teacher Galen Johnson.

Seattle Opera Lectures: We attended opera in Seattle for decades, and gradually grew in our understanding and appreciation of opera. From the late 1970s to the early 2000s, we continued off-and-on to take non-university courses dealing with opera, including (beginning in about 1999) the very enjoyable free lecture series offered through Seattle Opera on the campus of Seattle University. These consisted of presentations by Perry Lorenzo (who died much too young in 2009), Speight Jenkins, and others, discussing 19th Century Romantic Novels and Operas (1999), Shakespeare in Opera (1999), Verdi (2001 – 2002), and Wagner's Parsifal (2002 – 2003), etc. We also attended several of the mini-symposia Seattle Opera offered near the Opera House dealing with a particular upcoming opera, including Tristan und Isolde (1998), Barber's Vanessa (1999), and Britten's Billy Budd (2001).

Jazz Course: In a completely different genre, I also enjoyed Fred Radke's course on the history of jazz given at North Seattle Community College (Winter 2001). He had some fascinating tales to tell from his personal experiences as a trumpet player in the bands of jazz and dance-band luminaries, including Harry James and Glen Miller, as well as tales from the years of leading his own jazz band. (This course when I took it happened to coincide with the excellent 18-hour PBS series, Jazz: A Film By Ken Burns.)

Beginning in 2006, Becky and I embarked on a delightful and more substantial phase in our musical educations. At 60, we became eligible for the UW Access program, which has allowed us to audit several courses, including ones offered in other departments. (See here for a full listing of courses taken, and further discussion of the Access program.) The music courses have given me the chance to taste what it might have been like to major in music, something I would have considered had I been endowed with more talent and motivation. (But in fact, medicine is hard to beat for providing personal satisfaction.)

Physics of Music: In 2006, while I was still undergoing chemotherapy, Becky and I explored the physical and psychoacoustical foundations of music through Professor Vladimir Chaloupka's fascinating course on the Physics of Music (Physics 207, Spring 2006). This was our first course audited under the Access program. I had met the professor the previous fall while attending a medical symposium on "Music and the Brain". The excellent textbook—The Science of Sound, 3rd Edition by Rossing et al—left me impressed by how much the scientific knowledge in these fields had advanced since my reading of C. A. Taylor's enjoyable 1965 book, The Physics of Musical Sounds, forty years earlier. A highlight of the course was Vladi's fine performance of several excerpts from Bach's Die Kunst der Fuge [The Art of Fugue] on the Littlefield pipe organ at Kane Hall. He is a thoughtful philosophical scientist and artist, and Becky and I greatly enjoyed and learned much from this course. We recommend this course for students who enjoy music and want to know more about the physical phenomena which underlie it.

Music Theory and Musicianship (including Sightsinging): In 2006, we shifted back somewhat from a focus on opera to our earlier interests in the wider range of classical music, including purely orchestral or instrumental music. This was prompted by the UW course we audited, entitled Music Theory and Musicianship (Music 119, Autumn 2006), accompanied by an hour per week of sightsinging (Music 113). These truly challenging courses are intended for music majors, and not surprisingly, the bright kids we were surrounded by often ran circles around us. We were taught by the excellent Professor Áine Caitriona Heneghan, new to the faculty in 2006, hailing originally from Ireland. The theory course employs an interesting if sometimes mildly frustrating textbook by Steve Laitz (note 14), a textbook that is probably improved in its second edition. This text focuses on the tonal music of the so-called Common Practice Era of European art music c. 1600 – 1900 (particularly by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, etc.) In the first half of 2007, we attended the continuation of this important music theory course (Music 201 in Winter 2007, and Music 202 in Spring 2007), again taught by Professor Heneghan. It was very gratifying to learn more about the foundations of tonal music, especially such concepts as dissonance, harmony, and "voice leading", as well as the use of formulaic constructs such as cadences and phrases, etc. It was a great pleasure to catch this superb and knowledgeable teacher early in her UW teaching career. We continued to cross paths with her as a respected mentor and friend until she moved on in 2013 to the U. Michigan (a great loss for the UW), and we hope she will return to Seattle someday. We recommend these courses for serious students of music.

History of Western Music II and III: In 2007, we also enjoyed the exceptionally fast-moving course on the History of Western Music, Part II (MUHST 211, Winter 2007), which surveyed musical styles and developments in the 17th and 18th centuries. (The limited available time did not permit any more than a quick flyby of even the greatest of composers.) Part II was taught by Professor Stephen Rumph. We continued in Part III (MUHST 212, Spring 2007), covering the 19th and 20th centuries, and taught by Professor John Nelson. (We have so far not been allowed to audit Part I, which focuses on medieval and renaissance music.) These were perhaps the first courses I have taken in which full orchestral and piano reduction scores were routinely studied and analyzed at a skilled musician's level, although usually in excerpts. It was fascinating to see the appearance in full score of the revolutionary harmonies found in Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune [Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun], or the primitive and complex rhythms in the Danses des Adolescentes in Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps [The Rite of Spring]. Our textbook for Part III was the excellent Volume 2 of Norton Anthology of Western Music, 5th Edition by Burkholder and Palisca (a companion text to the Grout/Palisca History of Western Music). We also were especially impressed with DVD performances of: (1) Monteverdi's Orfeo (with musicians in period costume, conducted by Jordi Savall); (2) the Joffrey Ballet's reconstruction of Nijinksy's original choreography of Le Sacre du Printemps; and (3) Berg's Wozzeck. The highlight of Part III was a very engaging rock concert put on live in the classroom by Professor Larry Starr and John Hanford (both on electric guitar) and a pickup band consisting mostly of students plus some cameo appearances by other faculty including the Director of the School of Music. We recommend both courses as standard building blocks for a classical music education, though they leave you wanting much much more.

Opera and Politics: This music history course (MUHST 419, Autumn 2007) was taught by Professor Stephen Rumph, and dealt with the interplay of Opera and Politics at specific times in history and in specific operas. We focused on Gluck's reform opera Iphigénie en Tauride [Iphigenia in Tauris], Verdi's highly political Don Carlos, and Adams's The Death of Klinghoffer. It was courageous of Professor Rumph to choose the Adams work, a thought-provoking and deeply moving but controversial opera. (We watched the even more controversial 2003 movie version, directed by Penny Woolcock, on DVD.) This class was our first 400 level music course, and was attended by a number of advanced undergraduate and graduate music students—an impressive and inspiring group to be around. We recommend this course but space was limited.

American Popular Music History: We greatly enjoyed the course of Professor Larry Starr (photo above) on American Popular Music History (MUHST 426, Autumn 2008), for which he employs the fine textbook he co-authored, American Popular Music, 2nd Edition. This course really helped to fill in some major gaps in our music educations. It was rewarding to study popular music as a legitimate academic subject, and to better understand how popular music might fit into the broader picture of American music during the past 200 years or so. I especially enjoyed the Tin Pan Alley era, the origins of Rhythm and Blues, Swing Music, Rock 'N' Roll, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Folk and C&W Music, and the emphasis placed on such influential artists as Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, and Ray Charles. Professor Starr also touched on some of the practical and business aspects of being a professional musician or songwriter, and brought in a rising singer-composer, Laura Veirs. The class included several interesting and accomplished popular music musicians, who offered distinctly non-classical perspectives. We also made some nice friends in this entertaining class. We recommend this course.

The Lieder (Art Songs) of Johannes Brahms: This superb seminar-style course was taught by an acknowledged authority on Brahms, Professor George S. Bozarth (MUHST 417, Winter 2009). We were privileged to be allowed to sit in as "backbenchers" (it was a small somewhat crowded classroom). He reviewed the literary and cultural origins of lieder—"art songs" which had their golden age in the 19th century, at least in Germany and Austria—and the evolution of Brahms's thought, melancholic temperament, and artistic achievements. We covered many of Brahms's songs for solo voice and piano. Our favorites included Gestillte Sehnsucht [Quieted Longing], Geistliches Wiegenlied [Sacred Lullaby], and Dämmrung senkte sich von oben [Twilight has floated down]. We studied several of his duets, including the delightful Guter Rat [Good Advice, from mother to daughter]; ensemble vocal works (including the upbeat Liebeslieder Waltzer [Love Song Waltzes], and the more bitter Neue Liebeslieder [New Love Songs]); and the somewhat misanthropic Alt-Rhapsodie [Alto Rhapsody]. This was one of the most enjoyable and informative courses we have had the pleasure of taking, especially gratifying because I had never before made any serious effort to study Brahms—after all, he wrote no operas! The warm-hearted and courtly professor has a fine manner with advanced students and obviously loves teaching, including savoring the German language and the poetry on which these lieder are composed. He expected a high scholarly standard and required the use of a wide variety of assigned book and article resources, which gave me the opportunity to learn much more about how the UW library systems works. We were honored to attend a reception given in their home by Professor Bozarth and his wife Tamara Friedman, an accomplished keyboard player—they demonstrated several of their antique and faithfully reproduced keyboard instruments. We also were pleased to learn of and begin attending some of the well regarded non-UW Gallery Concerts series (for which he is the Artistic Director). To enhance class Gemütlichkeit, we met up for good schnitzel at a Seattle German restaurant, The People's Pub. Becky one day baked for the class a tasty marzipan stollen (which was lustily devoured). One of the graduate students in our class, Sarah Markovits, did a fine job singing the tragic role of Jephte's unnamed daughter in the Choral Arts performance of Carissimi's poignant Jephte, and we have heard several other of our classmates perform in other concerts. We recommend this course but space is very limited.

Sacred Music in the Lutheran Tradition (Baroque Choral Music): This seminar-style course was also taught by George S. Bozarth (MUHST 406, fall 2009). He began with the body of Lutheran chorales, many of which originated with the remarkably talented music lover and composer, Martin Luther—thank God for Luther's appreciation of music. We began with Michael Praetorius, Johann H. Schein, and Samuel Scheidt, and progressed to the influence of Claudio Monteverdi (for example, his Zefiro torna and Pulchra es), Dietrich Buxtehude (Cantata Jesu, meine Freude BUXWV 60), Friedrich Zachow, and Johann Kuhnau. This rich Baroque vocal and choral tradition culminated in Johann Sebastian Bach. We studied the trajectory of his life and career, focusing on several of his cantatas and other vocal works, particularly the chorale cantatas Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein (BWV 2), Christ lag in Todesbanden (BWV 4), and the majestic Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme (BWV 140), and concluded with his St. John and St. Matthew Passions. This was a well-taught and inspiring course dealing with some of our favorite music and composers, and some of the talented students were quite knowledgeable. I was pleased to find the inspiration to learn much more than I had previously known about J. S. Bach's life and works in general, and about some of the other musically-talented Bachs. We recommend this course but space is very limited.

The German Lied: Lieder (Art Songs) of Schubert and His Predecessors: Yet another outstanding seminar-style course taught by George S. Bozarth (MUHST 411, Spring 2010). He opened with an analysis of German language poetic forms used in lieder texts. We reviewed German song before 1750, including Minnelieder (by Minnesingers such as Walther von der Vogelweide), works of Meistersingers (such as Hans Sachs), and selected vocal music of J. S. Bach and Johann Hermann Schein. We examined the key role of the romantic writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (particularly Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre). And we touched on a number of other predecessors of Schubert including Handel, C. P. E. Bach, Johann F. Reichardt, Karl F. Zelter, Mozart, Joseph Haydn, Johann R. Zumsteeg, Johann Carl G. Loewe, and Beethoven. Franz Schubert was the culmination of this course, and we ended on his much admired song cycle Die schöne Müllerin. As always, Professor Bozarth required extensive readings from a rich diversity of authoritative sources, most of which are not found on the Web, thus encouraging a scholarly approach to learning. I enjoyed getting to know some of the students a little better during this course, including conductor/singer Phillip Tschopp and a talented harp graduate student, Tomoko Numa (who showed us how the classical harp is designed and played to Becky and me along with our new friend, music educator and fellow auditor Reiko Ito). We recommend this course but space is very limited.

The Choral Music of Johannes Brahms: Again by Professor Bozarth, clearly in his element (MUHST 418, fall 2010). After a review of German poetic meter and the Volksliedstrophe, we studied examples of predecessors and influences including Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (the Crucifixus from Missa Papae Marcelli), Josquin des Prez (Ave Maria), J S Bach (Cantata BWV 4), and Robert Schumann (Langsam movement of Symphony No. 4). We reviewed the Viennese artistic scene including Brahms's music directorship of the Society of Friends of Music (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde or Musikverein) and the painter Gustav Klimt, and also considered Brahms's freethinking religious views along with the decline and restoration of German Protestant church music in the 19th Century. We then followed the development of Brahms's choral works, including some of his early contrapuntal works such as the Missa canonica and Geistliches Lied Op. 30, his Ave Maria Op. 12 and other works for women's choir, his much beloved masterpiece Ein deutsches Requiem, the Alto Rhapsody, Nänie, Schicksalslied, Gesang der Parzen, and his final choral works including Fest- und Gedenksprüche op.109. We considered how Brahms fit generally into the more conservative end of the spectrum of composers of his era—conservative inasmuch as he often honored the traditions of the earlier Germanic composers while being tonally innovative, and was opposed to the more programmatic "music of the future" of the Lisztians and Wagnerians. This was a fine scholarly course filled with great music, and I hated to see it end. We recommend this course but space is very limited.

The Art Songs of Gabriel Fauré: This graduate level seminar (MUHST 509, Winter 2011) was taught by Professor Stephen Rumph, an intimate class with only three credit students. By Fauré's time, French art songs or lieder were called "Mélodies" (a term first popularized by Berlioz's 1829 Mélodies irlandaises). They were often performed in private or semi-public French salons rather than in concert halls. Professor Rumph is a skilled French speaker and pianist as well as a professionally performing tenor, and he brought to life the texts and music of these songs in part by performing excerpts. The course looked at the historical and cultural context, particularly the remarkable Parisian salon scene (a mixture of aristocratic, bourgeois, and artistic salons in which amateurs were often able to perform alongside professionals). We proceeded chronologically. Several of the early songs have texts by the revered Romantic poet Victor Hugo. We continued through most of his songs, including La bonne chanson [Verlaine] and the pantheistic La chanson d'Eve [Van Lerberghe]—two song cycles especially favored by Prof. Rumph. We did not have time to study his final cycles (Le Jardin clos, Mirages, and the intriguingly named and difficult L'Horizon chimérique [Jean de la Ville de Mirmont]). He stressed the influence of recurring leitmotifs and the integral role of the French texts, including the text painting of mood and setting by the music. We discussed the relevant French poetic movements, from French Romanticism to the classicizing Parnassianism and finally Symbolism. The poets utilized for his songs, none of whom I had studied before, included Victor Hugo, Théophile Gautier, Leconte de Lisle, Sully Prudhomme, Paul Silvestre, Maurice Maeterlinck, Charles Van Lerberghe, Charles Baudelaire, and most notably Paul Verlaine. Some of the poetry is truly sublime and "subversive", for example Verlaine's Clair de lune ("...the calm moonlight, sad and beautiful, / which sets the birds in the trees dreaming, / and makes the fountains sob with ecstasy...") An excellent and inexpensive resource for learning this music is the complete 4-CD set with Elly Ameling, Gérard Souzay, and Dalton Baldwin. Of the more than 110 Fauré' songs, I especially enjoyed Rêve d'amour Op. 5/2 (his "first masterpiece"); Automne Op. 18/3; Adieu Op. 21/2; Clair de lune Op. 46/2; Mandoline and the exquisite En sourdine from Cinq mélodies 'de Venise' Op. 58; N'est-ce pas? from La Bonne chanson Op. 61/8; and Mélisande's song {Op. post., reused as Crépuscule in La Chanson d'Ève Op. 95). However, many of his songs, especially the later ones, seemed repetitive or too abstruse or too harmonically complex for ready enjoyment by a non-musician, perhaps more so because of my lack of French language skills. Nevertheless, we were very grateful to be allowed to audit this specialized and highly technical course on a lesser-known composer. These songs, which perfectly suited Becky's French language skills, are the subject matter for an upcoming book by the professor. We recommend this course for French speakers who love song and are willing to explore unfamiliar territory.

Finding an American Voice: An innovative multidisciplinary course focusing on American paintings, poetry, and music, this was taught for the first time by Prof. Larry Starr (MUHST 497, Autumn 2011). His goal was to explore with the class what constitute the unique and/or characteristic attributes of Americans, what aspects of our history and geography shape our literature and art, and which composers have chosen to authentically represent the American Voice. We focused on poets Walt Whitman (Song of Myself), Robert Frost (A Boy's Will and North of Boston, etc.), and Carl Sandburg (Chicago Poems). For American paintings, we perused Prelinger's 2001 compilation of Smithsonian art, Scenes of American Life. Our composers included Ives (mostly his songs, especially the Seven Songs for Voice and Piano compiled by Copland, and other songs from his 114 Songs), Gershwin (focusing on Ferde Grofé's original orchestration of Rhapsody in Blue), and Copland's 1950 song cycle, Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson (about which Starr has written a definitive monograph). This was a fine and successful course which stretched our horizons, and we were pleased with the maturity and diverse talents of the students. We were all impressed by the unusually impassioned appeal made by Prof. Starr—following in the tradition of R. W. Emerson's The American Scholar—that Americans including ourselves should take a greater interest in and promote American artists and composers, particularly living composers, rather than incessantly trotting out Old World warhorses. (In our defense, Becky and I have cultivated an appreciation for currently living composers Philip Glass, John Adams, Ennio Morricone, and Alan Silvestri, but I also contend that music should be entertaining, fulfilling, or enriching in some way, and living composers ignore this obvious point at their own peril.)

Brahms's Chamber Music: Yet another excellent course taught by George S. Bozarth (MUHST 509, Autumn 2012). This was a seminar-style graduate course, and some of the material was beyond our level, especially the music theory (which drew on Brahms and the Principle of Developing Variation, by Walter Frisch). However, I enjoyed the opportunity to systematically learn more about this body of works about which I knew little initially, and also the expert playing by some of the gifted students including Rose Cheng and Brooks Tran. We recommend this course for persons willing to study advanced aspects of Brahms's chamber music, but space may be limited.

American Musical Theater (MUHST 497A, Autumn 2013): taught by Larry Starr. As with the other Starr courses that we have audited, this was a thoughtful and well presented course, and its subject was a diverse and vibrant body of music that we had never focused on before. We studied representative American musicals (stage and/or film), including: Show Boat (J. Kern and O. Hammerstein II, stage 1927, film 1936 dir. James Whale, on DVD); Anything Goes (Cole Porter, stage 1934, film 2010 revival, on DVD, also attended live performance of this revival show in Seattle 2013); Top Hat (film 1935 dir. Mark Sandrich, with F. Astaire and G. Rogers, on DVD); Singin' in the Rain (film 1952 dir. Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, includes Cyd Charisse, on DVD); Porgy and Bess (George & Ira Gershwin & DuBose Heyward, opera 1935, film 1993 dir. by Trevor Nunn, on DVD); Love Me Tonight (R. Rodgers & L. Hart, film 1932, dir. Rouben Mamoulian, on DVD); and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (S. Sondheim & H. Wheeler, stage musical 1979, film for TV 1982 with Angela Lansbury, DVD, sicko). Becky & I also took this opportunity to explore several other filmed American musicals on DVD, including several of the Astaire/Rogers films and Cabaret. We recommend this course for anyone interested in learning more about American musical theater.

Music in American Cultures (MUS 446/AES 446, Winter 2016): taught by Shannon Dudley. "Examines the music of minority and immigrant groups, or musical subcultures—including selected examples of the music of African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Jewish Americans, Asian Americans, and European Americans—that have fed into the American musical 'mainstream' or had significant popularity on its periphery. We will consider how ideas about race, ethnicity, class, as well as the music industry have conditioned the perception and experience of music; how certain performance genres have developed historically; and the meanings that music, or the experience of listening to and playing it, have for people." Specific genres touched on and notable examples included: minstrelsy (Thomas D. Rice); rags (Scott Joplin); blues and other black forms (Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, James Brown); jazz and bebop (black vs. white: Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie; Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman); ranchero, conjunto (Narciso Martinez), orquesta tejana (Beto Villa), Son Jarocho (Ritchie Valens: La Bamba), and Tejano of South Texas (Selena Gomez: Bidi Bidi Bom Bom); Chicano of LA (Quetzal); klezmer and the Jewish immigrant experience (drawing on Mark Slobin's Tenement Songs); and Asian (Butterfly Lover's Song).

Immigrant or ethnic instruments that we heard include:

East Asian: erhu (2 stringed bowed);

Eastern European:

tsimbl (hammered dulcimer or cimbalon);

Middle Eastern/Arab American: ud (oud, fretless pear-shaped lute); qanun (kanun, large plucked zither); nay (ney, an end-blown flute); riq (riqq; tambourine); darabukkah (goblet drum, vase-shaped drum with ceramic body); mizmar (single or double-reed folk oboe); mijwiz (single reed double-piped folk "clarinet"); tabl baladi (davul or tupan, double-headed drum);

Latino/Hispanic: claves (sticks); maracas (gourd rattle); guiro/güiro (notched gourd); marimba; marimbula (plucked box); quijada (jawbone with rattling teeth); conga (tall drum); bongo (dual small drums); tarima (stomp box); jarana jarocha (guitar from Veracruz); requinto jarocho (smaller quitar); tololoche (small bass); and bajo sexto (larger guitar);

African-American: banjo (banza); djembe (drum); Diddley bow; (single string); mbira (thumb piano); washtubs, mouth bow, kazoo (mirliton), etc.

(These ethnic musical forms and instruments warrant much more careful study than I have given them.)

This was the last course Rebecca and I took together prior to her death in July 2017.

Debussy and Ravel (MUHST 497B, Spring 2018): taught by Larry M. Starr. This was the first course I have had which focused on either of these extraordinarily gifted composers. It was very informative and touched on an extensive selection of the repertoire, not all of which was familiar. Debussy works studied or performed included: String Quartet in G minor (1893); Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune (1894); Pelléas et Mélisande opera (1893–1902); Images oubliées (1894); Nocturnes for orchestra (Nuages, Fêtes, and Sirènes including Female Choir, 1897–1899); Estampes (1903) including Pagodes; Danse sacrée et danse profane (1904); La mer, with movements De l'aube à midi sur la mer, Jeux de vagues, and Dialogue du vent et de la mer (1903–1905); Images, Set 1 for piano, especially Reflets dans l'eau (1905); Images, Set 2 for piano (1907); Préludes, Book 1 especially La cathédrale engloutie (1909–1910); Images pour orchestre (1905 - 1912);and Préludes, Book 2 for solo piano, especially Ondine and Feux d'artifice (1912–1913). Ravel works studied or performed included: Jeux d'eau for piano (1901); String Quartet in F (1902–03); Miroirs for piano (1904–05), including Alborada del gracioso (orchestrated 1918) and Une Barque sur l'océan (orchestrated 1906); Histoires naturelles, song cycle (1906); Rapsodie espagnole for orchestra (1907); Gaspard de la nuit for piano (1908), especially Ondine; Daphnis et Chloé ballet (1909–1912); Prélude for piano (1913); Le tombeau de Couperin for piano (1914–17), and orchestration of 4 parts (1919); L'Enfant et les sortilèges, lyric fantasy (1917-1925); La Valse, choreographic poem for orchestra (1919–20); Boléro for orchestra (1928); and Piano Concerto in G Major (1929–31). I especially enjoyed the opportunity of hearing so many of the talented students perform. It was obvious how much respect and enthusiasm the students have for Prof. Starr's teaching style. This was the first course I have taken since Rebecca's death, and she was greatly missed. She would have loved this course as well, and could have helped me with the French as we went along. I recommend this course for anyone interested in these composers, but must note that Prof. Starr is semi-retiring to 40%.

Music of Igor Stravinsky (MUHST 497A, Autumn 2018): taught by Larry M. Starr. Another of Starr's 400 level courses, this explored a representative selection of a single important composer's works, some of which were unfamiliar. Compositions studied included the well-known ballets (The Firebird, 1910 [orig. choreography Michel Fokine]; Petrushka, 1911 [also Fokine]; The Rite of Spring,1913 [orig. choreography Vaslav Nijinsky]; Pulcinella, 1920); lesser known ballets (Les noces, 1914–17; Apollo or Apollon musagète 1928; and Agon, 1957); his better known operas (L'Histoire du soldat, 1918; The Rake's Progress, 1951); and a variety of his other neoclassical and serial/atonal works (3 symphonies; Symphony of Psalms, 1930; Requiem Canticles, 1966; Mass, 1944-8; Violin concerto in D, 1931; other concertos; sonatas, chamber works such as Octet for Wind Instruments, 1923, Septet, 1953; etc.) We viewed videos of many of the staged works, including one of George Ballanchine teaching dancers his choreography of the Violin Concerto in D. Prof. Starr acknowledged that Stravinsky is anti-romantic in that he avoids expressing personal feelings, and can be a difficult composer, but though "some [of his works] we respect from a distance"), he is nonetheless worthy of study. My Stravinsky favorites remain the ballets. For me the serial/atonal works are never going to be on my short list (unless perhaps those that are accompanied by dance). However, I always enjoy the expertise, knowledge, and enthusiasm of the diverse students attending and contributing substantially to these advanced courses—choral conductors, music theorists, dance enthusiasts, and of course performing musicians. I recommend this course for anyone interested in Stravinsky, but Prof. Starr is semi-retiring as of 2019.

Beginning about 2007, we also attended several afternoon or evening music lecture presentations on the UW campus given by faculty and visiting professors. These have included an abstruse Music Theory lecture, and one on Music and Language Cognition (2008, by Professors Demorest, Morrison, and Osterhout). Perhaps I will attend more of these music lectures, although they tend to be quite technical.

During college and medical school, I turned occasionally to reading about music, and enjoyed especially the fine survey text on classical music by Grout, A History of Western Music. I returned to a successor of this first edition in 2000, reading with great enjoyment Grout and Palisca's 5th edition of A History of Western Music. Though still of necessity quite selective, as a single volume text must be, it was more extensive in its coverage than before, and was supplemented by the related two volume Norton Anthology of Western Music, 3rd Edition, complete with 12 CDs of very helpful recorded examples. I highly recommend these works, in their latest editions, to anyone interested in increasing their knowledge and understanding of classical music and more generally, the origins and evolution of western musical forms.

One especially helpful work to me, which I read in 1967, was C. A. Taylor's 1965 The Physics of Musical Sounds. I had recently graduated from college with a physics degree, and this book allowed me to explore in greater depth the fascinating world of music as a physical phenomenon. (See above regarding Rossing's updated physics text pertaining to this subject.)

Starting In the 1970s, with Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen and Tristan und Isolde setting the Seattle opera scene ablaze, I began to enjoy reading many fine works related to opera, especially Ernest Newman's instructive and indispensable 1949 The Wagner Operas and his adulatory magnum opus, The Life of Richard Wagner. For those willing to take the time to study some of the musical language that Wagner employs in telling his mature operatic stories (especially Tristan und Isolde, Der Ring des Nibelungen, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and Parsifal), it can be a wonderful and richly fulfilling exercise to learn some of the key leitmotifs (defined here) and how he so skillfully employed them. The librettos in German of course tell only a part of the story, sometimes a confused one, but the leitmotifs when superimposed on words and on each other can evoke wonderfully contradictory emotions and complex recollections, undergo endless transformations, and contribute to the musical and artistic brilliance for which this somewhat monstrous man is so justly revered. Best of all, you do not need to speak German to understand his musical language! I enjoyed putting together detailed study guides of Der Ring des Nibelungen, Tristan und Isolde, and Parsifal leitmotifs, complete with recorded excerpts and images of the relevant sections of the scores, and presented these in the form of HTML pages to friends and family as we prepared to attend upcoming performances.

It is Wagner's rich music and highly influential musical artistic ideals that I celebrate, not his bigoted beliefs and polemical writings. I happen to believe, as does for instance Daniel Barenboim, that a music lover should be prepared to make this separation. Though I became obsessed with and possessed by Wagner's music, and thus became a Wagnerite or Wagnerian, I have also enjoyed biographies of other favorite musical notables: J. S. Bach, Brahms, Berlioz, Mozart, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky, among others.

More recently, the Oxford Music Online website has become an invaluable Web resource to me and others to whom it is available. It includes Grove Music Online (derived from the venerable print edition of The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians), The Oxford Companion to Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

The Web of course now provides an almost inexhaustible storehouse of information about music. One of my favorite sites is the International Music Score Library Project/Petrucci Music Library. Here are to be found for viewing (and, where legal, for downloading) the full scores of a huge number of classic works, including for example many operas, the nine Bruckner's symphonies, Purcell's Ode for St. Cecilia's Day, all of Bach's Cantatas and the Messe H moll BWV 232, Brahms's Ein deutsches Requiem, Op.45, etc. The Freedb.org website has CD tracklist information about recorded works which is quite helpful for capturing audio files to disk.

The interested reader may wish to explore a resource I have created—a large listing of extant works of music. These are mostly but not exclusively classical works, ones that I have heard and enjoyed, or in a few cases that I wish to hear and learn more about. This list is derived from the McGoodwin Music database and is also linked to on that page. The compilation includes most of our favorite classical works—the ones mentioned on this page, operas we have attended, and many of the major choral and orchestral works we have heard. As we take courses on music, I gradually add many of the works studied to this list, including the jazz and popular music from these courses. The list is quite large, even though I have not attempted to reconstruct many of the works we heard at concerts before I created the parent database. Because the listing includes a simple rating system (1 to 10) for many of the works, the works of music that we recommend are apparent (usually those with ratings of 7 to 10).

Becky and I have tried to have a musical household and to share our passion for music with our children. As mentioned above, we steered them toward early training in Suzuki piano—a teaching methodology for which we have the highest praise—including the kind and gentle teaching of Peggy Swingle in Seattle. We also took them as children to several Sunday afternoon Seattle Symphony concerts (where the program was explained by the conductor, and they scribbled furiously on coloring projects to keep from being too bored), and to other concerts in the area, and in later years enjoyed taking them to some operas.

Wendy tried her hand at playing the violin in junior and early high school orchestra, but eventually decided her interests lay elsewhere.

Christie stayed with piano lessons for many years. However, she also took up choral singing in elementary school—in Rebecca Rottsolk's Northwest Girlchoir, a fine organization that has given many young Seattle area girls a nice start in singing and musical careers. We will always remember how warm and supportive Rebecca was to her girls, and her deeply felt emotionality about the music, particularly the lovely choral setting of the Irish Blessing:

May the road rise up to meet you,

May the wind be always at your back,

May the sun shine warm upon your face,

And the rains fall soft upon your fields,

And until we meet again,

May the Lord hold you in the palm of His hand.

After further satisfying choral experiences at Whitman College, Christie also was given the opportunity to participate in the Seattle Choral Company—founded and directed by Fred Coleman—which she enjoyed for several years. We have thrilled to hear some of the great and serious choral music performed by this fine organization, including (besides many of our old favorites already named) the Rachmaninoff Vespers (1998), Biebl's Ave Maria, Verdi's Requiem (1997), Duruflé's Requiem, Vaughan Williams's Mass in G minor (1997), Morten Lauridsen's O Magnum Mysterium, and many others.

As a family, we have listened to much music together, mostly on CDs, and also have often enjoyed trying to sing along together at Christmas and other times of celebration. Although we have a nice supply of vocal work scores of various difficulties, and can more or less sing the Biebl mentioned above and other modest vocal works, most of what we can do on short notice can be found in the United Methodist Hymnal. (To download MIDI files of carols and hymns, click here and then on the "Hymn Index" button.) Some of our family favorites include the carols Good King Wenceslas; Once in Royal David's City; Hark! the Herald Angels Sing; O Come, O Come, Emmanuel; and What Child Is This—as well as the hymns Let Us Break Bread Together; Break Forth, O Beauteous Heavenly Light; and O Sacred Head, Now Wounded. Usually Christie is playing our upright piano or keyboard, and we crowd in around her trying to get close enough to see the notes. I am doing my best to keep my croaky bass/baritone in tune while struggling to identify who is keeping the beat, enjoying greatly these magnificent and heartfelt creations while often wishing, as Salieri laments in Amadeus, that we had somehow been granted more of a musical gift.

While taking the physics of music class, I bought some tuner's tools (a tuning "hammer", wedge mutes, and electronic chromatic tuner, etc.) and made a college try at learning how to tune my own piano. This was interesting, relevant to our course, and genuinely educational, but left a professional piano tuner who came along later unimpressed. In 2008, we added a Yamaha XS8 electronic synthesizer to our formerly "acoustic" piano studio. This is probably an abomination to many piano purists, but in the right hands these elegant keyboard instruments can sound remarkably like a rich piano, a full-throated pipe organ, or an amazing array of other sampled and synthesized instruments. (And the synthesizer is always in tune!) Mastery will probably never be attainable for me—here my reach will always exceed my grasp, and I have simply indulged in a bit of Snoopy–Red Baron fantasy. I have hoped this synthesizer will help give me and Becky the needed boost in motivation to allow us to improve our skills as keyboard musicians, and to put into effect some of the music theory and lore we have been learning over the past few years. So far, I've barely scratched the surface with this device, but the potential to record and play back multiple MIDI-style tracks ("voices") shows promise. For instance, I'd like to experiment with the Brahms lied Gestillte Sehnsucht, using Becky's piano skills to record the piano and the viola parts as separate tracks, and then have Christie sing the alto role. The biggest problem with recording multiple overlaid tracks would probably be the metronomic regularity of playback inherent in this recording technique. I am pleased to report that as of 2011, Becky has for about a year been inspired to resume taking serious piano lessons, and now regularly plays the grand piano voice of the synthesizer.

I have always been a sucker for any movie, whether otherwise great or mediocre, that incorporates fine music of any type—as long as the harmonies are rich, the rhythms are interesting, and the duration of musical passages are sufficient to allow real thematic development and not just fleeting phrases. I mention some personal favorites to follow:

Classical and/or Orchestral Scores: For movies especially, there is often no hard and fast separation between classical and popular genres, and in any event I don't claim great expertise in the large body of movie music.

There have been some great movies made out of classical operas: Bergman's 1975 Magic Flute; Franco Zeffirelli's 1983 La Traviata and 1986 Otello; Syberberg's controversial 1982 Parsifal; and Monteverdi's L'Orfeo with J. Savall conducting, among others.

Some movies have had fine orchestral scores composed by then-living composers. Those that I have especially enjoyed have included: Copland's The Red Pony; Prokofiev's Aleksandr Nevsky; Philip Glass's Kundun; Ennio Morricone's The Mission; Alan Silvestri's Predator 2; Jerry Goldsmith's Chinatown; John Barry's Body Heat and Out of Africa; Virgil Thomson's Louisiana Story; Trevor Jones's The Last of the Mohicans; Christopher Gunning's Firelight; and some of the film scores of Danny Elfman including Men in Black and Edward Scissorhands.

Many movies have incorporated classical music as an effective major element: Amadeus; Elvira Madigan; Diva; Fantasia; 2001: A Space Odyssey; Apocalypse Now; A Room with a View; Moonstruck; Meeting Venus; etc. The list could go on and on, but other persons have compiled much better lists.

Musicals: Of course there have also been fine films made from great American (or British) "musicals". Favorites have included Kern and Hammerstein's Show Boat; Rodgers and Hammerstein's Carousel, Oklahoma!, The Sound of Music, and South Pacific; Lerner and Lowe's My Fair Lady; Bernstein and Sondheim's West Side Story; Galt Macdermot's Hair; and Lloyd Webber's Cats.